Bethel College, McKenzie, Tennessee. S. Marlo, MD: "Buy online Abana cheap no RX - Proven Abana online OTC".

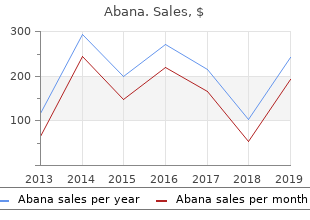

Participants were given a paper copy of the presentation slides for reference at the start of the focus group discussions order abana 60 pills mastercard total cholesterol ratio formula. All patient participants were given a £10 gift voucher after the focus group and travel costs were reimbursed cheap 60pills abana visa cholesterol levels lowering foods. Each focus group discussion was recorded and transcribed verbatim cheap abana 60 pills with amex does cholesterol medication make you drowsy. Ethics considerations Participants were asked at the start of each focus group discussion to not mention the names of staff or non-participants order abana 60 pills fast delivery cholesterol hdl ratio formula, and to respect the confidentiality of other participants. Researchers also informed patients that if they raised any questions in relation to their personal health issues during the focus group discussion, researchers could not respond to these and they were, therefore, advised to contact their GP. Data collection All focus groups were conducted using topic guides as a framework for discussions. Professional groups aimed to address the implementation of the PCAM tool within annual reviews of patients with the LTCs specified, along with determining any potential barriers to the use of the model and how these could be overcome. As the NPT was used as an analytic framework, the topic guides aimed to identify whether or not, and in what ways, nurses and other practice staff considered the PCAM to differ from existing ways of working; whether or not nurses and GPs could come to a collective agreement on the purpose of the PCAM; how practice staff understood what the PCAM required each of them to do; whether or not nurses and other practice staff constructed a potential value for the PCAM in the context of annual reviews; and whether or not nurses and other practice staff believed that the PCAM was an appropriate part of their work. Practical issues relating to the implementation of the embedded feasibility RCT and the PCAM in general were discussed to allow consideration to be given to how the individual requirements of different practices might be taken into account. This included discussion of what training may be needed to enable the use of the PCAM and how this could be delivered. Topics for discussion included what support patients needed to manage their conditions and whether or not primary care practitioners should play a role in helping them to manage life difficulties that might, potentially, have an impact on their health. The PCAM was then explained to patients and they were invited to discuss whether or not it was acceptable to them and whether or not they considered it useful in relation to their care. Patients were asked how PNs might best raise sensitive or difficult issues with them, and they were also asked about any potential barriers that nurses may experience in using the PCAM. Data analysis Data analysis involved constant comparison of key ideas/themes emerging from multiple staff reviews of focus group transcripts. Carina Hibberd, Eileen Calveley and Patricia Aitchison reviewed and compared patient and staff focus group transcripts as they became available. Data from staff and patient focus groups were organised separately within the database. Only designated members of the research team had access to the database. Carina Hibberd, Patricia Aitchison and Rebekah Pratt conducted initial, independent thematic analyses of focus group transcripts to devise a coding frame that was then discussed in detail by the wider analysis group (CH, PA, RP, EC and MM). Where required, analytical codes were amended at this stage by Rebekah Pratt, and descriptors were created to avoid duplication or lack of clarity in meaning. Rebekah Pratt recoded the entire data set based on the amended codes. For the purposes of this report, the key elements of analysis that are relevant to the acceptability and feasibility of using the PCAM tool in primary care-led annual reviews for LTCs, and for answering questions on the feasibility of a cluster RCT, are presented. The theory-driven NPT analysis will be presented in a future publication. Findings Recruitment of practices Figure 3 shows the number of GP practices contacted and subsequently recruited for focus group participation. Four practices agreed to take part in focus groups following telephone contact by researchers, two practices within NHS FV and two practices within NHS GGC. Our recruitment target for the number of focus groups was met. Recruitment to staff focus groups Sixteen health-care staff participated in the four focus groups. Participating health-care staff included PNs (n = 7), GPs (n = 3), PMs (n = 3), assistant PMs (n = 1) and administrative/reception staff (n = 2). The duration of staff focus group sessions ranged between 47 and 72 minutes. The four staff focus group sessions were held in the GP practice. Practices selected from ISD list [n = 98 (NHS FV 23, NHS GGC 75)] Practices excluded (n = 8) • Moved health board, n = 2 • LINKS, n = 5 • Too few nurses, n = 1 Practices invited by SPCRN [n = 90 (NHS FV 23, NHS GGC 66)] Practices declined (n = 4) Practices to be contacted by research team [n = 86 (NHS FV 20, NHS GGC 65)] Practices declined (n = 8) Practices excluded (n = 1) • Too few nurses, n = 1 Practices not contactable (n = 43) Practices contacted, not required (target achieved) (n = 30) Practices participating [n = 4 (NHS FV 2, NHS GGC 2)] FIGURE 3 The recruitment of practices to the focus group study. ISD, Information Services Division of National Services Scotland; LINKS, National Links Worker Programme (funded by the Scottish Government to make links between people and their communities through their GP practice). This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals 19 provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK. STUDY A: ACCEPTABILITY AND IMPLEMENTATION REQUIREMENTS OF THE PATIENT CENTRED ASSESSMENT METHOD Recruitment to patient focus groups Two of the four participating GP practices agreed to host a patient focus group. A total of 27 patients returned a note of interest, of whom one could not be directly contacted, seven declined or could not attend, two agreed but did not attend and 17 attended and consented. As intended, patient focus groups included a mix of age groups and sex, and reflected the social demographics of participating practices (Table 1). One patient focus group was held in the GP practice, and one patient focus group was held in a local community centre because of limited meeting space in the GP practice. The duration of each patient focus group was 105 minutes. Patient perceptions of living with a chronic illness Participants described the struggle of coming to terms with living with a chronic illness. Some described a tension between rejecting their diagnosis and accepting the limitations of their condition, and how that had an impact on their ability to manage their condition. Some had been told that they had DM, but felt that being asymptomatic made it hard to believe that they really did have the condition. Some described spending time, even years, in denial about their condition. This rejection of their condition led to avoidance of doctors, being scared of coming to the clinic, not taking medications and not looking after their health. One participant reflected on rejecting her condition after a negative experience with her GP, and is now facing serious kidney damage. Participants also reflected on the process of coming to terms with their condition, often describing a period of surprise followed by learning how to adjust and adapt to managing their condition. Some noted that there could be experiences that had a negative impact on their confidence, which may take some time to rebuild. Some described a longer process of having to come to terms with more than one condition, which may lead to more complications and care in managing their health. TABLE 1 Patient demographics (focus groups) Sex (n) Participants and demographics Male (N = 7) Female (N = 10) Age (years) range 66–83 47–83 Employment status Retired 5 6 Paid/self-employed 1 1 Housewife/husband 1 1 Voluntary work – 1 No data (long-term sickness) – 1 LTCa DM (type 1) 1 1 DM (type 2) 3 6 CHD 5 5 COPD 2 2 a Some patients had more than one LTC. Some were feeling generally well, but others were navigating more complex medical needs, such as surgery and therapies. Many reflected on various losses, such as limiting their food or activities. Participants also described feeling the need to just carry on and make the best of their situation.

Diseases

- Chronic bronchitis

- Blepharophimosis ptosis esotropia syndactyly short

- Hypokalemic sensory overstimulation

- Cholesterol pneumonia

- Encephalopathy intracerebral calcification retinal

- Fraser syndrome

There was less reflection of its use for less highly complex cases in which less urgent/severe problems could still be addressed to the benefit of patients abana 60 pills cholesterol ratio tc/hdl. However buy 60 pills abana visa cholesterol medication necessary, one practice had also begun to use a HoC approach by the second phase of the study generic abana 60 pills with visa cholesterol weight chart, prompting reflections on the two different approaches generic 60pills abana otc serum cholesterol ratio uk. In that practice, it was felt that the PCAM offered a tangible way of supporting patients, which complemented other approaches, and was revealing relevant and important patient issues. During an initial presentation of the PCAM study, one PN recounted that, as a Keep Well practice, PNs were already inviting patients to talk about well-being issues and that it was difficult to contain and manage these types of discussions within an appointment time limit. Concerns about issues being raised that could not be addressed through known resources contributed to this, and the resource pack element of the PCAM was welcomed, as it increased confidence in being able to offer some potential solutions. In training, several reminders to use the resource packs were needed during role plays. However, once PNs began to use the resource packs they praised the relevance of its contents and ease of use. There were many local suggestions for how to improve the resource packs and how they could or would take these forward once the PCAM study had ended. Most wanted a version they could control so that a practice could adapt it in the future. One practice reported that they were copying the resource packs for GPs to also use in consultations. The completion of the PCAM on paper was sometimes seen as an added burden, as it did not fit with the on-screen completion of other data collected during an annual review. This could feel like having multiple tasks to achieve in a consultation and the storage of additional paperwork then has to be considered. Practice interest and attention to psychosocial needs was very common in practices in the most deprived areas. However, even in less deprived practices, having one enthusiast for supporting psychosocial needs in the practice could help push others into trying the PCAM. The consideration of evidence within the process evaluation suggests that the PCAM is more likely to be feasible under the following conditions: l when nurses consider the asking of these questions to be part of the role of nursing l when nurses view their role as facilitating links to information or resources that can address concerns (rather than feeling that they have to address the concerns themselves) l when nurses have the information about resources available to them l when there is a whole-practice commitment to the approach, although in some large nurse-led units, this may be less important. Being aware of this was often helpful in opening discussion with nurses about potential benefits to their practice. A full explanation of each of the domains allowed nurses to consider cases in which touching on an issue might be of value, and increased interest in using the PCAM. The MDT meetings provided an opportunity for the PCAM to be used and discussed, and this helped practices to see the overall value to patients and PNs in using the PCAM. When this happened, nurses commented that it might then encourage the practice to continue to use the PCAM. The resource pack for facilitating signposting and referral was influential in securing practice participation, as it acted as an incentive; it provided nurses with a resource that they already recognised they needed, but did not have available in an easily accessible and LTC-focused format. The low-technology aspect of the paper-based version did appeal to users. Maintaining this resource would be integral to maintaining use of the PCAM. Some PNs reported that patient reluctance to take up referrals may limit the potential impact of the PCAM, reflecting that, in their view, patients were resistant to referrals because of real/perceived barriers, such as the cost and time of travel, shift patterns at work or childcare issues. However, it was recognised that such issues are not limited to the PCAM. Key learning for implementation of the Patient Centred Assessment Method Training in the use of the Patient Centred Assessment Method l There needs to be flexibility in how training and support is delivered. Brief training, followed by nurse reflection on the PCAM, alongside testing small areas of the PCAM and building up to its full use, can be interspersed with training/support sessions as nurses become more familiar and confident with the process or need to come back and ask questions. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals 65 provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK. Sometimes they do not broach an issue because they feel that they cannot help. Nurses need to be clear about their role in terms of signposting and referral, and have readily accessible resources to facilitate this. In some cases, the PM saw this as a role they could fulfil. Integrating the Patient Centred Assessment Method with practice systems l If the PCAM could be appended to the practice electronic record system for completion and storage, it may help to embed this within annual reviews and streamline the process. This would overcome problems of storage and could facilitate MDT access to the PCAM data, and actions being initiated by the practice. This would also allow any change and progress to be monitored. Implementation of the feasibility trial This analysis will focus on retention and study logistics in the multicentre sites and where any adaptations to protocol were identified. Recruitment and retention of practices Many of the reasons for non-recruitment have been presented in Chapter 4, and the same issues were also often responsible for nurse dropout. Although reported at a practice level, it was common across all practices for staffing issues, such as sickness absence or recruitment difficulties, to be a prime reason for not participating in the study or to result in delays in participating and implementing the PCAM. Even PMs felt that they lacked capacity to engage with the PCAM study when their practice had staff shortages. One PN had always indicated that the practice was not available to complete phase 2 data collection because of the uncertainty of future staffing levels in the practice beyond the summer of 2016; therefore, this practice was not included in the randomisation process. However, another practice failed to complete phase 2 data collection, initially because of staff sickness, and then subsequently because of additional pressures on practice resources, including the flu vaccination programme timing as well as perceived general under-resourcing. Every effort was made to accommodate postponement of phase 2 data collection and follow-up interviews, even up to and beyond the end date for the study, but, as each deadline for data collection approached, the practice reported that it would be unable to prioritise this within its current workload. The PCAM study and its data collection could not be prioritised over other practice issues; however, this practice has also indicated that it will continue to use the PCAM post study. Some practices expressed interest in participating on the basis of enthusiastic PNs who had received communication about the study and, in follow-up calls, were able to make the autonomous decision as to whether or not they wanted to learn more about the study. In some practices, GPs or PMs expressed concern that participation in research, even for quality improvement, would have a negative impact on workloads and place PNs under too much pressure. Having someone in the practice who was enthusiastic about participation and who understood the need to comply with study requirements made a big difference to completion rates. Nurses with an advanced level of nurse training and, previous research experience, and who were proactive in their local PN network had a greater understanding of the need to work within time scales and the study protocol. In some cases, the PM was proactive about identifying potential study recruits attending clinics; however, their absence from the practice for annual or sick leave had an impact on patient recruitment, particularly in phase 2. For privacy reasons, reception staff could not always reveal to the study team that the PM was absent and, therefore, contact with practices was hampered on occasion. This would indicate that any future study involving two phases of data collection would need to over-recruit practices to account for such attrition.

Syndromes

- Take acetaminophen every 4 - 6 hours.

- A diet high in meat products or cranberries can decrease your urine pH.

- Rapid breathing

- Pulmonary function tests

- Intrauterine device (IUD)

- Angioedema does not respond to treatment

- Inhaled medicines to help open the airways

The primate subtha- discharge to the amplitude and velocity of movement abana 60 pills mastercard cholesterol levels pediatric. The primate subtha- matics of reaching movements in two dimensions cheap abana 60 pills fast delivery cholesterol levels risk ratio. Changes in motor behavior and neuronal 1997;77:1051–1074 buy abana 60 pills low cost cholesterol know your numbers. Corticostriatal activity in primary vation in the MPTP model of parkinsonism effective abana 60pills cholesterol diet chart uk. Comparison of the mediating the control of movement velocity: a PET study. J effects of experimental parkinsonism on neuronal discharge in Neurophysiol 1998;80:2162–2176. MPTP-induced changes in spontaneous neuronal discharge in 298. Saccades and the internal pallidal segment and in the substantia nigra pars antisaccades in parkinsonian syndromes. Curr Opinion Neurobiol 1996;6: response properties of neurons in the 'motor' thalamus of 751–758. Physiologic properties hypokinetic and hyperkinetic movement disorders. Prog Neurol and somatotopic organization of the primate motor thalamus. Microelectrode-guided pal- behavioral effects of inactivation of the substantia nigra pars reticulata in hemiparkinsonian primates. Origins of post synaptic po- lidus (GP) of parkinsonian patients is similar to that in the tentials evoked in spiny neostriatal projection neurons by thala- MPTP-treated primate model of parkinsonism. Role of the basal ganglia in the initia- ley LJ, Koller W, eds. Prefrontostriatal connections in rela- of gabaergic inputs from the striatum and the globus pallidus tion to cortical architectonic organization in rhesus monkeys. J onto neurons in the substantia nigra and retrorubral field which Comp Neurol 1991;312:43–67. Cortico-striate projections in of cognition and of activation. Not all patients initially present with all of the individuals above the age of 55. In the two centuries since classic signs of the disorder; there may be only one or two. We have, for example, learned ness, and the cause is commonly misdiagnosed. However, where the primary lesion is and what many of the clinical postural deficits and tremor may soon emerge, prompting manifestations are. However, it has only been in the past a reconsideration of the basis of the problem. It is important few decades that insights have begun to emerge regarding to note, however, that the clinical diagnosis of PD is made the cause of the disease, and only now can one begin to see on the basis of a medical history and neurologic examina- the possibilities of treatments emerging that will provide tion; there is currently no laboratory test that can definitely more than temporary symptomatic relief. Even neuroimaging, which can be used the Nobel Prize–winning work of Arvid Carlsson, which to obtain an estimate of DA loss (15,128), is imperfect and pointed to the loss of dopamine (DA) as the principal deficit in any event is too expensive to be used as a routine diagnos- in PD and to levodopa as a mode of pharmacotherapy, we tic tool. As a result, it has been estimated that a significant have come to understand what fails in this disorder and, number of individuals diagnosed as having PD fail to show more recently, how we might correct that failure. Moreover, the histopathologic hallmarks of the disease upon autopsy although Parkinson focused entirely on motor symptoms, (48,70,134). We then cobasal ganglionic degeneration, and others (94). Rigidity describe the pathology before turning to several promising is a motor sign more often appreciated by the examining leads with regard to the underlying etiology of the disorder. It is often uniform in direc- tions of flexion and extension ('lead pipe rigidity'), but CLINICAL SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS there may be a superimposed ratcheting ('cogwheel rigid- Motor Manifestations ity'). Bradykinesia refers to a slowness and paucity of move- ment; examples include loss of facial expression, which may PD is a chronic, progressive neurologic disease. It presents be misinterpreted as a loss of affect, and associated move- with four cardinal motor manifestations: tremor at rest, ri- ments such as arm swinging when walking. Bradykinesia is not due to limb rigidity; it can be observed in the absence of rigidity during treatment. Zigmond: Departments of Neurology and Psychiatry, Univer- oropharynx, it can lead to difficulties in swallowing, which sity of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Burke: Department of Neurology, Columbia University, New in turn may cause aspiration pneumonia, a potentially life- York, New York. Of the cardinal motor signs, pos- 1782 Neuropsychopharmacology: The Fifth Generation of Progress tural instability is the most potentially dangerous, because have particular premorbid personality traits (126,129,152). It is also one of the For example, some have argued that they tend to follow manifestations that responds less well to levodopa therapy. Support for this hypothesis comes from a An additional motor feature of PD is the freezing phe- number of studies, including several involving twins that nomenon, also referred to as 'motor block' (51). Many of most typical form, freezing occurs as a sudden inability to these studies suffer from such problems as small sample step forward while walking. It may occur at the beginning size and retrospective analysis. Nonetheless, as noted at the ('start hesitation'), at a turn, or just before reaching the outset of this section, the anatomy of basal ganglia circuitry destination. It is transient, lasting seconds or minutes, and is consistent with a broad range of functions, and some of suddenly abates. Combined with postural instability, it can these could easily affect personality in subtle ways. Freezing does not always improve with levo- one, posit, for example, a 'rigid PD personality' that paral- dopa, and, in fact, can be made worse. The issue is an important one, not only for our understanding of PD and of the neuro- biology of behavior, but also because of the value of develop- Cognitive and Psychiatric Manifestations ing diagnostic screens that will permit the detection of PD at It is increasingly clear that there are many parallel circuits the earliest possible stage. Such early detection will become within the basal ganglia, each subserving a different function increasingly important as neuroprotective strategies emerge. Thus, it is reasonable to predict that patients will have a wide variety Other Manifestations of dysfunctions extending well beyond the classic motor In addition to these neurologic signs and symptoms, PD disabilities associated with the disease. Many PD patients also have signs of auto- of cognitive and psychiatric dysfunctions. Most common is nomic failure, including orthostatic hypertension, constipa- dementia and depression. However, hallucinations, delu- tion, urinary hesitancy, and impotence in men (90,107, sions, irritability, apathy, and anxiety also have been re- 133).