Fisk University. J. Corwyn, MD: "Order cheap Losartan online - Cheap Losartan no RX".

Nevertheless we should bear in mind generic 25mg losartan amex diabetes mellitus monitoring, first 25mg losartan otc diabetes type 1 log sheets, that especially in the period up to about 400 bce (the time in which most of the better-known Hippocratic writings are believed to have been produced) generic 25 mg losartan overnight delivery diabetes symptoms dizzy spells, ‘philosophy’ was hardly ever pursued entirely for its own sake and was deemed of considerable practical relevance buy generic losartan 50mg blood glucose values for newborns, be it in the field of ethics and politics, in the techni- cal mastery of natural things and processes, or in the provision of health and healing. Secondly, the idea of a ‘division of labour’ which, sometimes implicitly, underlies such a sense of surprise is in fact anachronistic. We may rightly feel hesitant to call people such as Empedocles, Democritus, Pythagoras and Alcmaeon ‘doctors’, but this is largely because that term conjures up associations with a type of professional organisation and spe- cialisation that developed only later, but which are inappropriate to the actual practice of the care for the human body in the archaic and classical period. The evidence for ‘specialisation’ in this period is scanty, for doctors 20 See, e. As we get to the Hellenistic and Imperial periods, the evidence of specialisation is stronger, but this still did not prevent more ambitious thinkers such as Galen or John Philoponus from crossing boundaries and being engaged in a number of distinct intellectual activities such as logic, linguistics and grammar, medicine and meteorology. It is no exaggeration to say that the history of ancient medicine would have been very different without the tremendous impact of Aristotelian science and philosophy of science throughout antiquity, the Middle Ages and the early modern period. Aristotle, and Aristotelianism, made and facilitated major discoveries in the field of comparative anatomy, physiology, embryology, pathology, therapeutics and pharmacology. They provided a comprehensive and consistent theoretical framework for re- search and understanding of the human body, its structure, workings and failings and its reactions to foods, drinks, drugs and the environment. They further provided fruitful methods and concepts by means of which medical knowledge could be acquired, interpreted, systematised and com- municated to scientific communities and wider audiences. And through their development of historiographical and doxographical discourse, they placed medicine in a historical setting and thus made a major contribu- tion to the understanding of how medicine and science originated and developed. Aristotle himself was the son of a distinguished court physician and had a keen interest in medicine and biology, which was further developed by the members of his school. Aristotle and his followers were well aware of earlier and contemporary medical thought (Hippocratic Corpus, Diocles of Carystus) and readily acknowledged the extent to which doctors con- tributed to the study of nature. This attitude was reflected in the reception of medical ideas in their own research and in the interest they took in the historical development of medicine. It was further reflected in the extent to which developments in Hellenistic and Imperial medicine (especially the Alexandrian anatomists and Galen) were incorporated in the later history of Aristotelianism and in the interpretation of Aristotle’s works in late anti- quity. Aristotelianism in turn exercised a powerful influence on Hellenistic and Galenic medicine and its subsequent reception in the Middle Ages and early modern period. Introduction 15 Yet although all the above may seem uncontroversial, the relationship between Aristotelianism and medicine has long been a neglected area in scholarship on ancient medicine. The medical background of Aristotle’s biological and physiological theories has long been underestimated by a majority of Aristotelian scholars – and if it was considered at all, it tended to be subject to gross simplification. These attitudes appear to have been based on what I regard as a misun- derstanding of the Aristotelian view on the status of medicine as a science and its relationship to biology and physics, and on the erroneous belief that no independent medical research took place within the Aristotelian school. Aristotle’s distinction between theoretical and practical sciences is sometimes believed to imply that, while doctors were primarily concerned with practical application, philosophers only took a theoretical interest in medical subjects. It is true that Aristotle was one of the first to spell out the differences between medicine and natural philosophy; but, as I argue in chapters 6 and 9, it is often ignored that the point of the passages in which he does so is to stress the substantial overlap that existed between the two areas. And Aristotle is making this point in the context of a theoretical, physicist account of psycho-physical functions, where he is wearing the hat of the phusikos, the ‘student of nature’; but this seems not to have prevented him from dealing with more specialised medical topics in different, more ‘practical’ contexts. That such more practical, specialised treatments existed is suggested by the fact that in the indirect tradition Aristotle is credited with several writings on medical themes and with a number of doctrines on rather specialised medical topics. And as I argue in chapter 9, one of those medical works may well be identical to the text that survives in the form of book 10 of his History of Animals. Such a project would first of all have to cover the reception, transformation and further development of medical knowledge in the works of Aristotle and the early Peripatetic school. This would comprise a study of Aristotle’s views on the status of medicine, his characterisation of medicine and medical practice, and his use and further development of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, physiology and embryology; and it would also have to comprise the (largely neglected) medical works of the early Peripatos, such as the medical sections of the Problemata and the treatise On Breath, as well as the works of Theophrastus and Strato on human physiology, pathology and embryology. It would further have to examine the development of medical thought in the Peripatetic school in the Hellenistic period and the reception of Aristotelian thought in the major Hellenistic medical systems of Praxago- ras, Herophilus, Erasistratus and the Empiricists. Thirdly, it would have to cover the more striking aspects of Galen’s Aristotelianism, such as the role of Aristotelian terminology, methodology, philosophy of science, and tele- ological explanation in Galen’s work; and finally, it would have to consider the impact of developments in medicine after Aristotle – for example the Alexandrian discoveries of the nervous system and of the cognitive function of the brain, or the medical theories of Galen – on later Aristotelian thought and on the interpretation of Aristotle’s biological, physiological and psy- chological writings in late antiquity by the ancient commentators, such as Alexander of Aphrodisias, Themistius, Simplicius and John Philoponus, or by authors such as Nemesius of Emesa and Meletius of Sardes. This is a very rich and challenging field, in which there still is an enormous amount of work to do, especially when artificial boundaries between medicine and philosophy are crossed and interaction between the two domains is con- sidered afresh. It is concerned with what I claim to be an Aristotelian discussion 24 In addition to older studies by Flashar (1962) and (1966) and Marenghi (1961), see the more recent titles by King, Manetti, Oser-Grote, Roselli, Fortenbaugh and Repici listed in the bibliography. Introduction 17 of the question of sterility, a good example of the common ground that connected ‘doctors’ and ‘philosophers’, in which thinkers like Anaxagoras, Empedocles, Democritus and Aristotle himself were pursuing very much the same questions as medical writers like the author of the Hippocratic embryological treatise On Generation/On the Nature of the Child/On Diseases 4 or Diocles, and their methods and theoretical concepts were very similar. But Aristotle’s medical and physiological interests are also reflected in non-medical contexts, in particular in the fields of ethics and of psycho- physiological human functions such as perception, memory, thinking, imagination, dreaming and desire. In the case of Aristotle’s theory of sleep and dreams, too, there was a medical tradition preceding him, which he explicitly acknowledges; but as we will see in chapter 6, his willingness to accommodate the phenomena observed both by himself and by doctors and other thinkers before him brings him into difficulties with his own theoretical presuppositions. A similar picture is provided by the psychology and pathology of rational thinking (ch. And, moving to the domain of ethics, there is a very in- triguing chapter in the Eudemian Ethics, in which Aristotle tries to give an explanation for the phenomenon of ‘good fortune’ (eutuchia), a kind of luck which makes specific types of people successful in areas in which they have no particular rational competence (ch. Aristotle tackles here a phe- nomenon which, just like epilepsy in On the Sacred Disease, was sometimes attributed to divine intervention but which Aristotle tries to relate to the human soul and especially to that part of the soul that is in some sort of intuitive, instinctive way connected with the human phusis – the peculiar psycho-physical make-up of an individual. Thus we find a ‘naturalisation’ very similar to what we get in his discussion of On Divination in Sleep (see chapter 6). Yet at the same time, and again similar to what we find in On the Sacred Disease, the divine aspect of the phenomenon does not completely disappear: eutuchia is divine and natural at the same time. This is a remarkable move for Aristotle to make, and it can be better understood against the background of the arguments of the medical writers. Moreover, 18 Medicine and Philosophy in Classical Antiquity the phenomenon Aristotle describes has a somewhat peculiar, ambivalent status: eutuchia is natural yet not fully normal, and although it leads to success, it is not a desirable state to be in or to rely on – and as such it is comparable to the ‘exceptional performances’ (the peritton) of the melan- cholic discussed in chapter 5. We touch here on yet another major theme that has been fundamental to the development of European thought and in which ancient medicine has played a crucial role: the close link be- tween genius and madness, which both find their origin in the darker, less controllable sides of human nature. The fact that many of these writers and their works have, in the later tradition, been associated with Hippocrates and placed under the rubric of medicine, easily makes one forget that these thinkers may have had rather different conceptions of the disciplines or contexts in which they were working. Thus the authors of such Hippocratic works as On the Nature of Man, On Fleshes, On the Nature of the Child, On Places in Man and On Regimen as well as the Pythagorean writer Alcmaeon of Croton emphatically put their investigations of the human body in a physicist and cosmological framework. Some of them may have had very little ‘clinical’ or therapeutic interest, while for others the human body and its reactions to disease and treatment were just one of several areas of study. Thus it has repeatedly been claimed (though this view has been disputed) that the Hippocratic works On the Art of Medicine and On Breaths were not written by doctors or medical people at all, but by ‘sophists’ writing on technai (‘disciplines’, fields of systematic study with practical application) for whom medicine was just one of several intellectual pursuits. Be that as it may, the authors of On Regimen and On Fleshes, for instance, certainly display interests and methods that correspond very neatly to the agendas of people such as Anaxagoras and Heraclitus, and the difference is of degree rather than kind. A further relevant point here is that what counted as medicine in the fifth and fourth centuries bce was still a relatively fluid field, for which rival definitions were continuously being offered. There was very considerable diversity among Greek medical people, not only between the ‘rational’, Introduction 19 philosophically inspired medicine that we find in the Hippocratic writings on the one hand and what is sometimes called the ‘folk medicine’ practised by drugsellers, rootcutters and suchlike on the other, but even among more intellectual, elite physicians themselves. One of the crucial points on which they were divided was precisely the ‘philosophical’ nature of medicine – the question of to what extent medicine should be built on the foundation of a comprehensive theory of nature, the world and the universe. It is interesting in this connection that one of the first attestations of the word philosophia in Greek literature occurs in a medical context – the Hippocratic work On Ancient Medicine – where it is suggested that this is not an area with which medicine should engage itself too much.

Syndromes

- Scores 8 through 10: High-grade cancer.

- Motor skills

- Headache

- Constantly seeking reassurance or approval

- A history of using blood thinners or a bleeding disorder

- Problems breathing

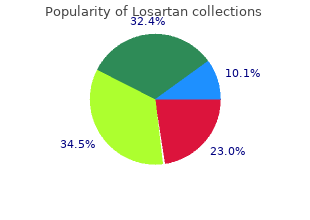

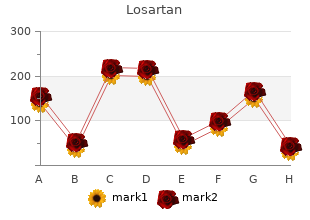

Collectively discount losartan 50mg with mastercard diabetes diet sheet pdf, these results suggest that the new treatment is more effective than the standard treatment’ losartan 25 mg mastercard diabete 097. A curve is then plotted for each group by calculating the proportion of patients who remain in the study and who are censored each time an event occurs cheap 50mg losartan free shipping diabetes mellitus aafp. Thus discount losartan 25mg otc diabetes symptoms dog, the curves do not change at the time of censoring but only when the next event occurs. The survival plot shows the proportion of patients who are free of the event at each time point. The steps in the curves occur each time an event occurs and the bars on the curves indicate the times at which patients are censored. The sections of the curves where the slope is steep, in this case the earlier parts, indicate the periods when patients are most at risk for experiencing the event. It is always advisable to plot survival curves before conducting the tests of significance. There are several ways to plot survival curves and the debate about whether they should go up or down and how the y-axis should be scaled continues. Using the commands Edit → Select X Axis in the Chart Editor, the range of the x-axis and other properties of the plot such as chart size can be changed. Plotting survival curves is not problematic when the study sample is large and the follow-up time is short. However, when the number of patients who remain at the end is small, survival estimates are poor. It is important to end plots when the number in follow-up has not become too small. Therefore, in the above example, the curves should be truncated to 31 days when the number in each group is 10 or more and should not be continued to 65 days when all patients in the standard treatment group have experienced the event or are censored. Thescalingofthey-axis is important because differences between groups can be visu- ally magnified or reduced by shortening or lengthening the axis. In practice, a scale only slightly larger than the event rate is generally recommended to provide visual discrimination between groups rather than the full scale of 0–1. However, this can tend to make the differences between the curves seem larger than they actually are, for example in a plot in which the y-axis scale ranges from 0. For example, in predicting an event such as death, factors such as age of the patient or number of years smoking cigarettes can be included in a Cox regression model. Compared to the Kaplan–Meier method where only categorical variables can be used to predict the event, with the Cox regression analysis a combination of categorical and/or continuous variables can be used to predict survival. Cox regression is similar to other regression models such as linear regression or logistic regression (see Chapters 7 and 9, respectively), in that regression coefficients are gener- ated, interaction between variables can be examined and adjustment for confounding factors can be made. A rule of thumb is that Cox models should have a minimum of 10 outcome events per predictor variable. In Cox regression analysis, the dependent variable is the hazard function at a given time. With a Cox regression analysis, the effect of each covariate is reported as a hazard ratio. The hazard ratio is computed as the proportion of the rate (or function) of the hazard in the two groups. The hazard ratio can be used to estimate the hazard rate in a treatment group compared to the hazard rate in the control group. A hazard ratio of 2 indicates that, at any time point, twice as many patients in the one group experience an event compared with the other group. It is important to note that a hazard ratio of 2 does not mean that patients in the treated group improved or healed twice as quickly as patients in the control group. The correct interpretation of a hazard ratio of 2 is that a patient, who has been treated and has not improved by a certain time, has twice the chance of improving at the next time point compared to a patient in the control group. Regression coefficients are also generated for the explanatory variables or covariates that are included in the model. In building the Cox regression model, as in multiple linear regression (see Chapter 7), there are a number of different methods for including covariates in the model. The enter option can be used to enter variables all at once or to sequentially add variables in blocks. The inclusion or removal of variables is based on the corresponding statistics calculated. As with multi- ple linear regressions, it is important that both the clinical and statistical significance of variables be considered in building a parsimonious model. The hazard ratio is sometimes used interchangeably to mean a relative risk (see Chapter 9); however, this interpretation is not correct. The hazard ratio incorporates the change over time, whereas the relative risk can only be computed at single time points, generally at the end of the study. That is, the haz- ard (rate of the event) in one group should be a constant proportion of the hazard in the other study group over all time points. This assumption is important since the haz- ard ratio estimated by the model is for all time points. If the curves are proportional and approxi- mately parallel, then the assumption of proportional hazards is met. If the curves cross or if curves are not parallel and diverge they indicate that the rate of the event between the two groups is different (e. How- ever, with small data sets the error around the survival curve is increased and therefore this test may not be accurate. More appropriate methods are the log-minus-log plot12 and examination of the partial residuals. The log-minus-log of the survival function, is the ln(−ln(survival)), versus the survival time. The residuals when plotted should be horizon- tal and close to zero (shown later in the chapter) if the hazards are proportional. Null That there is no difference in survival rates between treatment groups hypothesis: or gender groups. Variables: Outcome variable = death (binary event) Explanatory variables = time of follow-up (continuous), treatment group (categorical, two levels), gender (categorical, two levels) The commands shown in Box 12. Categorical Variable Codingsa Frequency (1) Genderb 1=Male 25 1 2=Female 31 0 aCategory variable: gender (gender). Block 1: Method = Enter Omnibus Tests of Model Coefficientsa Change from Change from −2Log Overall (score) previous step previous block likelihood Chi-square df Sig. The Omnibus Tests of Model Coefficients tests the null hypothesis that all effects are equal to zero. The table reports the chi-square value for the overall model (a measure of goodness of fit), as well as the change from the previous model and the corresponding significance level.

Syndromes

- Eye disease, such as inflammation of the retina (chorioretinitis)

- Drawing a square

- Metronidazole

- Myocarditis

- Changes in organ function

- Portal vein obstruction

- Itching

- Have your blood pressure checked every 2 years unless it is 120-139/80-89 Hg or higher. Then have it checked every year.

- Injury to the area between the scrotum and anus (perineum)

- Take the drugs your doctor told you to take with a small sip of water.

Although it is still in widespread use around the world it is gradually becoming obsolete cheap 50mg losartan amex gene therapy cures diabetes in dogs. Other drugs There are other oral sedative drugs that are commonly reported in the literature in relation to paediatric dental sedation cheap losartan 25mg overnight delivery diabetes mellitus awareness questionnaire. These include: hydroxyzine hydrochloride and promethazine hydrochloride (psychosedatives with an antihistaminic cheap 25mg losartan otc diabetes type 2 zonder medicatie, antiemetic cheap 25mg losartan visa diabetes treatment centers, and antispasmodic effect), and ketamine which is a powerful general anaesthetic agent which, in small dosages, can produce a state of dissociation while maintaining the protective reflexes. Common side-effects of hydroxyzine hydrochloride and promethazine hydrochloride are dry mouth, fever, and skin rash. Side-effects of ketamine include hypertension, vivid hallucinations, physical movement, increased salivation, and risk of laryngospasm, advanced airway proficiency training is, therefore, essential. Ketamine carries the additional risk of increase in blood pressure, heart rate, and a fall in oxygen saturation when used in combination with other sedatives. Evidence to support the single use of either hydroxyzine hydrochloride, promethazine hydrochloride, or ketamine is poor. Monitoring during oral sedation This involves alert clinical monitoring and at least the use of a pulse oximeter. The technique is unique as the operator is able to titrate the gas against each individual patient. That is to say, the operator increases the concentration to the patient, observes the effect, and as appropriate, increases (or sometimes decreases) the concentration to obtain optimum sedation in each individual patient. The administration of low-to-moderate concentrations of nitrous oxide in oxygen to patients who remain conscious. The precise concentration of nitrous oxide is carefully titrated to the needs of each individual patient. As the nitrous oxide begins to exert its pharmacological effects, the patient is subjected to a steady flow of reassuring and semi-hypnotic suggestion. This means that it is not possible to administer 100% nitrous oxide either accidentally or deliberately (the cut- off point is usually 70%). This is an important and critical clinical safety feature that is essential for the operator/sedationist. In addition to the machine head that controls the delivery of gases, it is also necessary to have a suitable scavenging system, and an assembly for the gas cylinders, either a mobile stand (Fig. The actual percentage of gases being delivered is monitored by observing the flow meters for oxygen and nitrous oxide, respectively (Fig. When the patient breathes out the reservoir bag gets larger as it fills with the mixture of gases emanating from the machine. Wait 60 s, above this level the operator should exercise more caution and consider whether further increments should be only 5%. With experience, operators will be able to judge whether further increments are needed. To bring about recovery turn the mixture dial to 100% oxygen and oxygenate the patient for 2 min before removing the nasal mask. The patient should breathe ambient air for a further 5 min before leaving the dental chair. The patient should be allowed to recover for a total period of 15 min before leaving. The above method of administration is the basic technique that is required in the early stages of clinical experience for any operator. This method ensures that the changes experienced by the patient do not occur so quickly that the patient is unable to cope. The initial time intervals of 60 s are used because clinical experience shows that shorter intervals between increments can lead to too rapid an induction and over- dosage. By careful attention to signs and symptoms experienced by the patient the dentist will soon be able to decide whether the patient is ready for treatment. The very rapid uptake and elimination of nitrous oxide requires the operator to be acutely vigilant so that the patient does not become sedated too rapidly. If the patient tends to communicate less and less, and is allowing the mouth to close, then these are signs that the patient is becoming too deeply sedated. The concentration of nitrous oxide should be reduced by 10 or 15% to prevent the patient moving into a state of total analgesia. This applies to only a very small proportion of patients such as those with cystic fibrosis with marked lung scarring or children with severe congenital cardiac disease where there is high blood pressure or cyanosis. It is important to note that different patients exhibit similar levels of impairment at different concentrations of nitrous oxide. If the patient appears to be too heavily sedated then the concentration of nitrous oxide should be reduced. There is no need to use pulse oximetry or capnography (to measure exhaled carbon dioxide levels) as is currently recommended for patients being sedated with intravenously administered drugs. The machinery At all stages of inhalation sedation, it is necessary to monitor intermittently the oxygen and nitrous oxide flow meters to verify that the machine is delivering the gases as required. In addition, it is essential to look at the reservoir bag to confirm that the patient is continuing to breathe through the nose the nitrous oxide gas mixture. Little or no movement of the reservoir bag suggests that the patient is mouth breathing, or that there is a gross leak, for example, a poorly fitting nasal mask. Plane 1: moderate sedation and analgesia This plane is usually obtained with concentrations of 5-25% nitrous oxide (95-75% oxygen). As the patient is being encouraged to inhale the mixture of gases through the nose, it is necessary to reassure him or her that the sensations described by the clinician may not always be experienced. The patient may feel tingling in the fingers, toes, cheeks, tongue, back, head, or chest. There is a marked sense of relaxation, the pain threshold is raised, and there is a diminution of fear and anxiety. The patient will be obviously relaxed and will respond clearly and sensibly to questions and commands. Other senses, such as hearing, vision, touch, and proprioception, are impaired in addition to the sensation of pain being reduced. The peri-oral musculature, so often tensed involuntarily by the patient during treatment, is more easily retracted when the dental surgeon attempts to obtain good access for operative work. The absence of any side-effects makes this an extremely useful plane when working on moderately anxious patients. Plane 2: dissociation sedation and analgesia This plane is usually obtained with concentrations of 20-55% nitrous oxide (80-45% oxygen). As the patient enters this plane, psychological symptoms, described as dissociation or detachment from the environment, are experienced. It may also take the form of a euphoria similar to alcoholic intoxication (witness the laughing gas parties of the mid-nineteenth century). Apart from the overall appearance of relaxation, one of the few tangible physical signs is a reduction in the blink rate.