Principia College. C. Hamid, MD: "Order Haldol online - Trusted Haldol online".

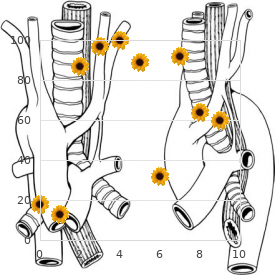

The band is then secured to the adventitia of the pulmonary artery at various intervals with interrupted 6-0 or 5-0 Prolene sutures discount 5 mg haldol visa 5 medications related to the lymphatic system. The main pulmonary artery is isolated purchase 10 mg haldol symptoms after miscarriage, and the Silastic band is passed around it and narrowed as described previously buy haldol 5 mg on-line medical treatment. Regular suture material or a narrow band may cut through and produce hemorrhage that is difficult to control buy haldol 10mg on line medications like adderall. Difficulty Passing the Band around the Pulmonary Artery It may be easier and safer to initially pass the tape around both the aorta and pulmonary artery through the transverse sinus and then between the aorta and pulmonary artery. Troublesome Bleeding Small adventitial vessels on the aorta and pulmonary artery may give rise to troublesome bleeding; they must be identified and cauterized. Excessive Banding the degree of banding must not be too constrictive because this will result in unacceptable cyanosis and possible hemodynamic collapse. Inadequate Banding Many times, the tightness of the band is limited by the hemodynamic response of the patient. To limit the pulmonary blood flow in these patients, ligation of the pulmonary artery or a Damus-Kaye-Stansel anastomosis and shunt procedure may be required (see Chapter 30). Early Reoperation to Adjust Band It is not uncommon to leave the operating room with a suitable band, only to have the patient develop signs that the band is too tight or too loose in the early postoperative period. Placing the Band Too Proximally If the band is placed too proximally, the sinotubular ridge of the pulmonic valve will be distorted. To adequately relieve the gradient during the debanding procedure, the sinus portion(s) of the pulmonary root often needs to be patched. This is especially problematic when an arterial switch or Damus-Kaye-Stansel procedure is planned at the second stage. Band Migration the band should be sewn to the adventitia of the proximal aspect of the main pulmonary artery. This precaution prevents the band from migrating distally, narrowing the pulmonary artery at its bifurcation and obstructing the right, left, or both branches. After the optimal band constriction has been achieved, it is secured and the pericardium is approximated with multiple interrupted sutures. A punch is taken from the center of this disc, whose diameter is roughly the size of a shunt appropriate for the baby by weight. A transverse, partial pulmonary arteriotomy is made halfway between the pulmonary root and the bifurcation, and through this partial incision, the backwall of the Gore-Tex “washer” is sewn using a running Prolene. As this is continued anteriorly, the Gore-Tex is included in between the two edges of the cut pulmonary artery. This technique has the advantage of (1) a controlled source of pulmonary blood flow and (2) eliminating the possibility of either band migration or pulmonary valve damage. This device is capable of repeated narrowing and releasing of the pulmonary artery at the bedside, avoiding reoperation. Because of its elliptic shape, there usually is no need for reconstruction of the pulmonary artery when the device is removed. It may be necessary to reconstruct the pulmonary artery to eliminate any gradient across the band site. When a Silastic band has been in place for a short time, simple removal of the band often results in no gradient. If a pressure gradient or obvious deformity is noted at the band site, the pulmonary artery is repaired with the patient on cardiopulmonary bypass. An appropriately sized patch of glutaraldehyde-treated autologous pericardium or Gore-Tex is then sewn onto the defect with a continuous 5-0 or 6-0 Prolene suture. Persistence of the Gradient Inadequate enlargement of the main pulmonary artery may be responsible for persistence of the gradient across the site of the band. Alternatively, the portion of the main pulmonary artery involved in the banding can be resected and an end-to- end anastomosis performed between the proximal main pulmonary artery and the confluence of the right and left pulmonary arteries. Pulmonary Valve Insufficiency When the band has caused distortion of the sinotubular ridge, patching anteriorly into one sinus only often causes valvular insufficiency. If the patient will not tolerate pulmonary valve incompetence, the pulmonary artery can be transected and all three sinuses patched as described for supravalvular aortic stenosis (see Chapter 24). Incorporation of the Band into the Pulmonary Artery With the passage of time, the band may burrow through the wall of the pulmonary artery to become subendothelial. The band can be divided anteriorly but left in situ and the pulmonary artery enlarged with a patch angioplasty. Occasionally, the band may migrate distally to the pulmonary artery bifurcation and cause distortion of its branches. The incision on the pulmonary artery is then extended distally onto the left or both the left and right pulmonary artery branches as needed. Sizing the Patch the pericardial patch should be wide enough, particularly at its distal end, to prevent a residual gradient. The ascending aorta gives rise to right and left arches that encircle the trachea and esophagus and rejoin to form the descending thoracic aorta. Technique the left lung is retracted anteriorly and inferiorly toward the diaphragm to bring into view the area of the aortic arch and ductus arteriosus or ligamentum. The parietal pleura is incised longitudinally on the anterior surface of the descending aorta and left subclavian artery. The pleural flap containing the vagus nerve and its branches is retracted anteriorly; meticulous dissection is carried out to identify the local anatomy precisely. The surgeon should be aware that pulling the nerve toward the pulmonary artery causes the recurrent nerve to lie along a diagonal course behind the ductus or ligamentum, thereby increasing the risk of injury to the nerve. Adhesions of the Esophagus and Trachea Both the trachea and the esophagus must be dissected free of any adhesions and fibrous bands to ensure that narrowing of these structures is relieved. Division of Ductus or Ligamentum the ductus arteriosus or ligamentum must always be doubly ligated and divided. It is also important to resect any adjacent scar tissue that could contribute to postoperative tethering or scar. Injury to the Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve the vagus and recurrent laryngeal nerves are identified so that they are not inadvertently divided or traumatized. Division of the Smaller Arch the smaller of the two arches should be divided, otherwise a pseudocoarctation may develop. As a precaution, blood pressure cuffs should be placed on one leg and both arms and a trial occlusion of the smaller arch should be carried out to confirm the absence of a pressure gradient before dividing it. Aortopexy Some advocate tacking the suture line of the descending aorta toward the lateral chest wall fascia so as to open up the area of the ring “like a book” and thereby prevent postoperative impingement or scar. The ligamentum arteriosum extends from the superior aspect of the main pulmonary artery to the undersurface of the aortic arch. Hypoplasia of the distal trachea, with or without complete cartilaginous rings, is present in approximately 50% of these patients. Incision Although this lesion can theoretically be approached through a left thoracotomy and repaired without the use of cardiopulmonary bypass, stenosis and occlusion of the left pulmonary artery have been seen with this technique.

The abdominal examination may show firmness discount haldol 1.5 mg without a prescription medicine jar paul mccartney, distension generic haldol 5mg medications used to treat adhd, and the presence of hyperactive or hypoactive bowel sounds discount haldol 5mg visa medications kidney failure. In some cases buy haldol 5mg visa medicine allergic reaction, fecal impaction may present as diarrhea with incontinence when fecal material higher in the colon is broken down into liquid form and flows past the mass. Patients with traumatic spinal cord injury often have neurogenic bowel, but clinicians may overlook it in nontraumatic etiologies such as multiple sclerosis, stroke, or cancer. In these patients, digital rectal and abdominal exams can help distinguish between upper motor neuron (a tight anal sphincter with peristalsis intact) and lower motor neuron lesions (a flaccid sphincter with no volitional contraction). In upper motor neuron injury, evacuation depends on stimulating the bowel wall digitally or with a suppository; by comparison, patients with lower motor neuron injury may need stool-bulking agents like fiber to control stool flow [23]. A plain abdominal radiograph can estimate the stool burden and differentiate between obstruction and constipation. In patients with continued symptoms and concern of alternative etiologies, computed tomography may aid in evaluation of small bowel obstruction, ileus, intra-abdominal abscess, bowel perforation or undiagnosed intraluminal or extraluminal abdominal masses. Treatments It can be effective to time medication use with a patient’s normal toileting schedule and take advantage of the gastrocolonic response with meals to improve outcomes. Hydration and high dietary fiber content are advantageous for healthy, active patients; however, additional dietary fiber such as psyllium may worsen constipation and should generally be avoided for critically ill patients who are not well hydrated. If constipation due to secondary causes is suspected, interventions aimed at treating and reversing underlying etiologies should be attempted. Pharmacologic therapies that utilize different mechanisms and combine oral and rectal interventions may yield effective results. The early use of supportive therapeutic agents is important and can be initiated independent of underlying pathology and bowel habits (see Table 35. Magnesium salts must be used cautiously in renal insufficiency as this may lead to magnesium toxicity. Lactulose passes unabsorbed into the colon where bacteria break it down, thus possibly causing bloating and abdominal cramping. Sodium phosphate enemas should be used with caution among elderly patients as they may cause hypotension, volume depletion, and electrolyte loss [24]. Metoclopramide is a prokinetic agent that antagonizes dopamine receptors, and it can be used in constipation that has not responded to other pharmacologic interventions. Methylnaltrexone is a peripheral opioid antagonist with limited ability to cross the blood–brain barrier and thus does not reverse centrally mediated analgesia. It is approved for treatment of opioid-induced constipation among patients with advanced illness and is effective for inducing laxation of palliative care patients with opioid-induced constipation where conventional laxatives have failed [25]. Nausea is a subjective sensation that precedes the need to vomit and may be associated with other symptoms including tachycardia, lightheadedness, diaphoresis, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Retching is contraction of the abdominal musculature in the presence of a closed glottis and no expulsion of gastric contents. Any of these symptoms in the most severe form may result in electrolytes imbalances, dehydration, and feeding intolerance with subsequent malnutrition. The vomiting center additionally activates efferent pathways to the cranial nerves, diaphragm, and abdominal muscles [26,27]. Secondary causes of symptoms are adverse effects from medications, shock, abnormal lab values, renal failure, intracranial lesions, increased intracranial pressure, heart failure, and nonabdominal surgery [19]. Assessment Evaluation of nausea and vomiting in the critical care setting must involve patient assessment and corroboration of information from nursing staff. A thorough evaluation of the history, physical examination, laboratory, and radiographic data can frequently identify an etiology. Key components to assess are as follows: Symptoms of nausea, vomiting, retching, reflux, diarrhea, distension, abdominal pain, regurgitation, and constipation Timing, frequency, nature of the event (i. Bilious or fecal emesis associated with abdominal discomfort and constipation or absence of bowel movements can suggest bowel obstruction. Ileus occurs after abdominal surgery, and general anesthesia also contributes to nausea among postoperative patients. Treatment A successful approach to managing the symptomatic patient incorporates thorough patient assessment, knowledge of the emetic pathophysiologic pathways, and a comprehensive treatment plan including pharmacologic and emotional support [26]. Published guidelines currently focus on chemotherapy-related and postoperative nausea management [27,28]. The occurrence of encephalopathy during critical illness may result in clinicians treating signs of emesis rather than symptoms. Although targeted antiemetic treatment blocks the neurotransmitters implicated in the underlying cause, empiric therapy may be necessary without a clear etiology, usually with a dopamine or serotonin antagonist [26]. Phenothiazines are D antagonists but have broader activity than do2 metoclopramide, as they additionally block cholinergic and histamine receptors. These drugs have potent antiemetic activity, but are frequently associated with adverse effects including hypotension, sedation, dry mouth, and extrapyramidal effects. Prochlorperazine, promethazine, chlorpromazine, and levomepromazine are several phenothiazines that are available. Among terminal cancer patients, it is commonly used for the management of nausea and vomiting, and it has also been used for postoperative nausea and vomiting [29]. More recently, there has been interest in the atypical antipsychotic olanzapine for chronic nausea and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Their use is established for the prevention and treatment of nausea with chemotherapy and also in the postoperative patient [27,31]. Glucocorticoids are effective in chemotherapy-related and postoperative nausea, as well as in malignant bowel obstruction and elevated intracranial pressure from brain tumors. If nausea and vomiting is suspected due to corticosteroid insufficiency during acute illness, treatment with intravenous corticosteroids should be initiated. Delirium, which can be hyperactive, hypoactive, or mixed, is associated with increased morbidity and can be a sign of impending death of terminally ill patients. Delirium can also interfere with the assessment and management of other physical and psychological symptoms, such as pain. Assessment Unfortunately, delirium (especially the hypoactive form) is often misdiagnosed and therefore untreated in terminally ill patients. Patients with advanced illness have multiple physiologic disturbances that can cause delirium, and many etiologies are irreversible in dying patients. However, there are common reversible etiologies as well, including constipation, urinary retention, and medication side effects for this population [34]. For determining reversibility of delirium, a clinician should review the patient’s principal diagnosis, comorbidities, prognosis, and preadmission and current functional status. It is essential to hold a family meeting (including the patient if he or she is able to participate) in order to explain the nature of delirium, explore patient’s goals and priorities, and weigh the benefits against burdens of further evaluation to elucidate the underlying causes (see Table 34. Among other cases, the patient and family may decline a therapeutic trial or workup based on poor prognosis and/or need for burdensome testing, and delirium becomes effectively irreversible [34]. These modifiable risk factors include polypharmacy, environmental factors (such as noise and sleep interruptions), and social interaction with visitors and the health care team. Numerous studies have found that the use of dexmedetomidine in place of benzodiazepines or propofol results in a lower risk of delirium, but none have compared it with placebo [40]. The goals of symptom management are to keep a delirious patient safe and comfortable, while supporting and educating the family.

Wang C-C discount 10 mg haldol visa symptoms xanax withdrawal, Wang S-H buy 1.5mg haldol amex symptoms magnesium deficiency, Lin C-C cheap haldol 10 mg line medicine 3604, et al: Liver transplantation from an uncontrolled non-heart-beating donor maintained on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation best 1.5 mg haldol medications qd. Siminoff L, Arnold, R: Increasing organ donation in the african- american community: altruism in the face of an untrustworthy system. Azoulay D, Didier S, Castaing D, et al: Domino liver transplants for metabolic disorders: experience with familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. Azoulay D, Castaing D, Adam R, et al: Transplantation of three adult patients with one cadaveric graft: wait or innovate. Starzl T, Teperman L, Sutherland D, et al: Transplant tourism and unregulated black-market trafficking of organs. Matesanz R, Marazuela R, Domínguez-Gil B, et al: the 40 donors per million population plan: an action plan for improvement of organ donation and transplantation in Spain. Guidelines for the determination of death: Report of the medical consultants on the diagnosis of death to the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Inspector General: Medicare Conditions of Participation for organ donation: An early assessment of the new donation rule. The Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology: Practice parameters for determining brain death in adults. Taniguchi S, Kitamura S, Kawachi K, et al: Effects of hormonal supplements on the maintenance of cardiac function in potential donor patients after cerebral death. Niemann, C, Feiner J, Swain S, et al: Therapeutic hypothermia in deceased organ donors and kidney-graft function. Schnuelle P, Berger S, De Boer J, et al: Effects of catecholamine application to brain-dead donors on graft survival in solid organ transplantation. Schnuelle P, Gottmann U, Hoeger S, et al: Effects of donor pretreatment with dopamine on graft function after kidney transplantation. Kotsch K, Ulrich F, Reutzel-Selke A, et al: Methylprednisolone therapy in deceased donors reduces inflammation in the donor liver and improves outcome after liver transplantation. Perez-Blanco A, Caturla-Such J, Canovas-Robles J, et al: Efficiency of triiodothyronine treatment on organ donor hemodynamic management and adenine nucleotide concentration. Roels L, Pirenne J, Delooz H, et al: Effect of triiodothyronine replacement therapy on maintenance characteristics and organ availability in hemodynamically unstable donors. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Dimopoulou I, Tsagarakis S, Anthi A, et al: High prevalence of decreased cortisol reserve in brain-dead potential organ donors. Pienaar H, Schwartz I, Roncone A, et al: Function of kidney grafts from brain-dead donor pigs: the influence of dopamine and triiodothyronine. Washida M, Okamoto R, Manaka D, et al: Beneficial effect of combined 3,5,3-triiodothyronine and vasopressin administration on hepatic energy status and systemic hemodynamics after brain death. Goarin J-P, Cohen S, Riou P, et al: the effects of triiodothyronine on hemodynamic status and cardiac function in potential heart donors. Schwartz I, Bird S, Lotz Z, et al: the influence of thyroid hormone replacement in a porcine brain death model. Koller J, Wieser C, Gottardis M, et al: Thyroid hormones and their impact on the hemodynamic and metabolic stability of organ donors and on kidney graft function after transplantation. Mariot J, Sadoune L-O, Jacob F, et al: Hormone levels, hemodynamics, and metabolism in brain dead organ donors. Follette D, Rudich S, Bonacci R, et al: Importance of an aggressive multidisciplinary management approach to optimize lung donor procurement. Clark A, Bown E, King T, et al: Islet changes induced by hyperglycemia in rats: effects of insulin or chlorpropamide therapy. Revollo J, Cuffy M, Witte D, et al: Case report: hemolytic anemia following deceased donor renal transplantation associated with tranexamic acid administration for disseminated intravascular coagulation. Korb S, Albornoz G, Brems W, et al: Verapamil pretreatment of hemodynamically unstable donors prevents delayed graft function post-transplant. Other studies have calculated a projected 10-year survival benefit for an average cadaveric kidney transplantation [2]. More than just survival benefit, a successful transplantation can free a patient from the demands of dialysis and provide a higher quality of life at a fraction of the overall cost compared to those not transplanted [3]. The half- life graft survival is projected for deceased donor recipients to be 10 years; for living-related donor recipients, almost 18 years [4,5]. Enthusiasm for kidney transplantation is undoubtedly fueled by these promising outcomes; however, a donor shortage crisis remains. These protracted waiting times subject our patients to a great deal of harm from the ill effects of uremia and dialysis. Critical care providers, therefore, are facing a cohort of patients awaiting kidney transplantation who are sick and getting sicker. This chapter discusses the salient points of critical care to optimize outcomes after kidney transplantation. It is therefore imperative that the pretransplant evaluation should be exhaustive (covering cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, neurologic, genitourinary, and infection disease concerns). The goal is not only that the patient should survive the operation and hospitalization, but also survive in the long term so that there is a realization of the potential graft life of the donor allograft. The cardiovascular examination is the most important because cardiac events constitute the most common cause of death in the perioperative and postoperative periods [7]. Ironically, our preoperative screening with noninvasive cardiac stress testing is notoriously unreliable. In a meta- analysis, the sensitivity of the pretransplant cardiac perfusion study for myocardial infarction was only 0. The onus remains on the transplant clinician to be highly suspicious of potential cardiac morbidity, even in younger patients with prolonged renal failure. Abnormalities detected by stress testing require coronary angiography to investigate the need for coronary stenting or even coronary artery bypass. It may also be reasonable to perform coronary angiography on high-risk patients with significant comorbidities or a pronounced history of cardiac problems with unremarkable stress testing. Recurrent urinary tract infections or bladder dysfunction requires urodynamic testing and urology consultation. Abnormal results require hematology consultation and a plan for therapeutic measures in the perioperative period. In addition to electrolyte screening, a complete history and physical examination, electrocardiogram, chest X-ray, and laboratory examination should be performed just prior to the operation to uncover any possible health derangements since the last physician visit. Intraoperative Care the degree of invasive monitoring during the operation should reflect the extent of the recipient’s comorbidities. Central venous catheters are commonly introduced to guide intraoperative and postoperative fluid management. Continuous arterial blood pressure monitoring is also quite common and facilitates blood pressure management during the case. It is justified when recipients have significant cardiac dysfunction, valvular abnormalities, or significant pulmonary artery hypertension. A 20-F three-way Foley catheter is useful to inflate the bladder with saline that greatly facilitates the ureteroneocystostomy.

When changing dressings and tapes buy 10mg haldol with amex symptoms to pregnancy, special care is needed to avoid accidental dislodging of the tracheostomy tube buy 10mg haldol free shipping treatment hyponatremia. Sutures haldol 10 mg without a prescription medicine hat jobs, placed either for fixation and/or through the rings themselves for exposure haldol 1.5mg with mastercard symptoms 3dp5dt, should be removed as soon as practical, usually after 1 week when an adequate stoma has formed, to facilitate cleaning the stomal area. Malodorous tracheal “stomatitis” that can lead to an enlarging stoma around the tube should be treated with topical antimicrobial dressings such as 0. Significant induration and/or cellulitis should be managed with a systemic antibiotic such as clindamycin. Occasionally, the secretions become extremely malordorous, indicating a gram-negative or anaerobic infection or overgowth: this should be treated with topical and systemic antimicrobials. In other tracheotomy tubes, inner cannulas serve to extend the life of the tracheostomy tubes by preventing the buildup of secretions within the tracheostomy. The inner cannulas can be easily removed and either cleaned or replaced with a sterile, disposable one. Disposable inner cannulas have the advantage of quick and efficient changing; a decrease in nursing time; decreased risk of cross-contamination; and guaranteed sterility. The obturator should be kept at the bedside at all times in the event that reinsertion of the tracheostomy is necessary. Because tracheostomies bypass the upper airway, it is vital to provide patients who have tracheostomies with warm, humidified air. Failure to humidify the inspired gases can result in obstruction of the tube by inspissated secretions, impaired mucociliary clearance, and decreased cough. Suctioning Patients with tracheostomies frequently have increased amounts of airway secretions coupled with decreased ability to clear them effectively. Keeping the airways clear of excess secretions is important for decreasing the risk of lung infection and airway plugging [65]. Suction techniques should remove the maximal amount of secretions while causing the least amount of airway trauma. In the patient who requires frequent suctioning because of secretions, who otherwise appears well, without infection and without tracheitis, the tube itself may be the culprit. Downsizing the tube or even a short trial (while being monitored) with the tube removed may result in significantly less secretions, obviating the need for the tube. In fact, there may be significant risks associated with routine tracheostomy tube changes, especially if this is performed within a week of the initial procedure and by inexperienced caregivers. A survey of accredited otolaryngology training programs suggested a significant incidence of loss of airway and deaths associated with routine changing of tracheostomy tubes within 7 days of initial placement, especially if they are changed by inexperienced physicians [67]. In general, the tube needs to be changed only under the following conditions: (a) there is a functional problem with it, such as an air leak in the balloon; (b) when the lumen is narrowed because of the buildup of dried secretions; (c) when switching to a new type of tube; or (d) when downsizing the tube prior to decannulation. Patients who have their tracheostomy tube changed before the tract is fully mature risk having the tube misplaced into the soft tissue of the neck. If the tracheostomy tube needs to be replaced before the tract has had time to mature, the tube should be changed over a guide, such as a suction catheter or tube changer with personnel and equipment readily available at the bedside to perform orotracheal intubation if needed. Oral Feeding and Swallowing Dysfunction Associated with Tracheostomies Caution should be exercised before initiating feedings by mouth in patients with tracheostomy, because numerous studies have demonstrated that patients are at a significantly increased risk for aspiration when a tracheostomy is in place. Physiologically, patients with tracheostomies are more likely to aspirate because the tracheostomy tube tethers the larynx, preventing its normal upward movement needed to assist in glottic closure and cricopharyngeal relaxation. Tracheostomy tubes also disrupt normal swallowing by compressing the esophagus and interfering with deglutition, decreasing duration of vocal cord closure and resulting in uncoordinated laryngeal closure [68,69]. In addition, prolonged translaryngeal intubation can result in swallowing disorders that persist even after the endotracheal tube is converted to a tracheostomy [70]. It is therefore not surprising that between 40% and 65% of patients with tracheostomies aspirate when swallowing [71]. Before attempting oral feedings in a patient with a tracheostomy, several objective criteria must be met. The patient should have adequate cough and swallowing reflexes; adequate oral motor strength; and a significant respiratory reserve. However, bedside clinical assessment may only identify 34% of the patients at high risk for aspiration [72]. Augmenting the bedside swallowing evaluation by coloring feedings or measuring the glucose in tracheal secretions does not appear to increase the sensitivity in detecting the risk of aspiration [73]. A video barium swallow may identify between 50% and 80% of patients with tracheostomies who are at a high risk to aspirate oral feeding [72]. A laryngoscopy to observe directly a patient’s swallowing mechanics, coupled with a video barium swallow, may be more sensitive in predicting which patients are at risk for aspiration [72]. Plugging of the tracheostomy [67] or using a Passy–Muir valve may reduce aspiration in patients with tracheostomies who are taking oral feedings, but this is not a universal finding [75]. We believe that the potential risks of a percutaneous endoscopically placed gastrostomy feeding tube or maintaining a nasogastric feeding tube are much less than the risk of aspiration of oral feedings and its complications (i. Factors found to be associated with increased mortality in patients not decannulated prior 2 to transfer include body mass index greater than 30 kg per m and tenacious secretions. We suggest that patients with tracheostomies can be safely cared for in the general ward, provided there is an interprofessional team approach between physicians, nurses, and respiratory therapists. These complications are best grouped by the time of occurrence after the placement and are divided into immediate, intermediate, and late complications (Table 9. The reported incidence of complications varies from 4% [79] to 39% [19], with reported mortality rates from 0. Complication rates decrease with increasing experience of the physician performing the procedure [81]. Posttracheostomy mortality and morbidity are usually caused by iatrogenic tracheal laceration, hemorrhage, tube dislodgment, infection, or obstruction [3]. Tracheostomy is more hazardous in children than in adults, and carries special risks in the very young, often related to the experience of the surgeon [82]. A comprehensive understanding of immediate, intermediate, and late complications of tracheostomy and their management is essential for the intensivist. There is conflicting evidence regarding the complication rate of percutaneous tracheostomy in these patients. Additionally, the rate of severe complication in the obese group was nearly five times that of those in the nonobese group [84]. Overall, these studies are limited by the small numbers; retrospective or observational nature; and lack of long-term follow-up. Should that fail, it may be necessary to remove the outer cannula also, a decision that must take into consideration the reason the tube was placed and the length of time it has been in place. Obstruction may also be caused by angulation of the distal end of the tube against the anterior or posterior tracheal wall. An undivided thyroid isthmus pressing against the angled tracheostomy tube can force the tip against the anterior tracheal wall, whereas a low superior transverse skin edge can force the tip of the tracheostomy tube against the posterior tracheal wall.