Metropolitan State University. X. Sancho, MD: "Order Terazosin online - Cheap Terazosin no RX".

Yoga has been found to be especially helpful in relieving stress and in improving overall physical and psychological wellness buy generic terazosin 1 mg on line blood pressure ranges low normal high. It is believed that yoga breathing—a deep cheap terazosin 1 mg without a prescription pulse pressure treatment, diaphramatic breathing—increases oxygen to the brain and body tissues cheap 1 mg terazosin amex heart attack jack ps baby, thereby easing stress and fatigue and boosting energy cheap terazosin 5 mg amex pulse pressure 53. Individuals who practice the meditation and deep breathing associated with yoga find that they are able to achieve a profound feeling of relaxation. Hatha yoga uses body postures, along with the meditation and breathing exercises, to achieve a balanced, disciplined workout that releases muscle tension, tones the internal organs, and energizes the mind, body, and spirit, to allow natural healing to occur. The complete routine of poses is designed to work all parts of the body—stretching and ton- ing muscles and keeping joints flexible. Studies have shown that yoga has provided beneficial effects to some individuals with back pain, stress, migraine, insomnia, high blood pressure, rapid heart rates, and limited mobility (Sadock & Sadock, 2007; Steinberg, 2002; Trivieri & Anderson, 2002). Evidence has shown that animals can directly influence a person’s mental and physical well-being. Many pet-therapy programs have been established across the country and the numbers are increasing regularly. Several studies have provided information about the positive results of human interaction with pets. Another study revealed that animal-assisted therapy with nursing home residents significantly reduced loneliness for those in the study group (Banks & Banks, 2002). One study of 96 patients who had been admitted to a cor- onary care unit for heart attack or angina revealed that in the year following hospitalization, the mortality rate among those who did not own pets was 22% higher than that among pet owners (Whitaker, 2000). Some researchers believe that animals may actually retard the aging process among those who live alone. Loneliness often results in premature death, and having a pet mitigates the ef- fects of loneliness and isolation. Whitaker (2000) has suggested: Though owning a pet doesn’t make you immune to illness, pet own- ers are, on the whole, healthier than those who don’t own pets. Study after study shows that people with pets have fewer minor health problems, require fewer visits to the doctor and less medication, and have fewer risk factors for heart disease, such as high blood pressure or cholesterol levels (p. It may never be known precisely why animals affect humans they way they do, but for those who have pets to love, the thera- peutic benefits come as no surprise. Pets provide unconditional, nonjudgmental love and affection, which can be the perfect an- tidote for a depressed mood or a stressful situation. The role of animals in the human healing process requires more research, but its validity is now widely accepted in both the medical and lay communities. Most complementary therapies consider the mind and body connection and strive to enhance the body’s own natural healing powers. More than $27 billion a year is spent on alternative medical therapies in the United States. This chapter examined herbal medicine, acupressure, acu- puncture, diet and nutrition, chiropractic medicine, therapeutic touch, massage, yoga, and pet therapy. Nurses must be familiar with these therapies, as more and more clients seek out the heal- ing properties of these complementary care strategies. The separation from loved ones or the giving up of treasured possessions, for whatever reason; the experience of failure, either real or perceived; or life events that create change in a familiar pattern of existence—all can be experienced as loss, and all can trigger behaviors associated with the grieving pro- cess. Loss and bereavement are universal events encountered by all beings who experience emotions. A significant other (person or pet) through death, divorce, or separation for any reason. Examples include (but are not limited to) diabetes, stroke, cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, hearing or vision loss, and spinal cord or head injuries. Some of these conditions not only incur a loss of physical and/or emotional wellness but may also result in the loss of personal independence. Developmental/maturational changes or situations, such as menopause, andropause, infertility, “empty nest” syndrome, aging, impotence, or hysterectomy. A decrease in self-esteem, if one is unable to meet self-expectations or the expectations of others (even if these expectations are only perceived by the individual as unfulfilled). Separation from these familiar and per- sonally valued external objects represents a loss of material extensions of the self. Some texts differentiate the terms mourning and grief by describing mourning as the psychological process (or stages) through which the individual passes on the way to successful adaptation to the loss of a valued object. Grief may be viewed 390 Loss and Bereavement ● 391 as the subjective states that accompany mourning, or the emo- tional work involved in the mourning process. For purposes of this text, grief work and the process of mourning are collectively referred to as the grief response. Theoretical Perspectives on Loss and Bereavement (Symptomatology) Stages of Grief Behavior patterns associated with the grief response include many individual variations. However, sufficient similarities have been observed to warrant characterization of grief as a syndrome that has a predictable course with an expected resolution. Early theorists, including Kübler-Ross (1969), Bowlby (1961), and Engel (1964), described behavioral stages through which indi- viduals advance in their progression toward resolution. Some individuals may reach acceptance, only to revert to an earlier stage; some may never complete the sequence; and some may never progress beyond the initial stage. William Worden (2009), offers a set of tasks that must be processed to complete the grief response. He suggests that it is possible for a person to accomplish some of these tasks and not others, resulting in an incomplete bereavement and thus impairing further growth and development. Behaviors associated with each of these stages can be observed in individuals experiencing the loss of any concept of personal value. Feelings associated with this stage include sadness, guilt, shame, helplessness, and hopelessness. Self-blame or blam- ing of others may lead to feelings of anger toward the self and others. The anxiety level may be elevated, and the in- dividual may experience confusion and a decreased ability to function independently. The individual attempts to strike a bargain with God for a second chance or for more time. This is a very painful stage, dur- ing which the individual must confront feelings associated with having lost someone or something of value (called reactive depression). Feelings associ- ated with an impending loss (called preparatory depression) are also confronted. Examples include permanent life- style changes related to the altered body image or even an impending loss of life itself. Regression, withdrawal, and social isolation may be observed behaviors with this stage. Therapeutic intervention should be available, but not imposed, and with guidelines for implementation based on client readiness.

Usage: q.2h.

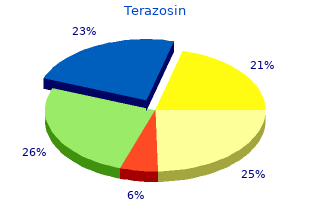

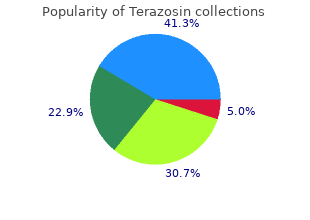

A further study by King (1982) examined the relationship between attributions for an illness and attendance at a screening clinic for hypertension discount 2mg terazosin free shipping blood pressure medication 30 years old. The results demon- strated that if the hypertension was seen as external but controllable by the individual then they were more likely to attend the screening clinic (‘I am not responsible for my hypertension but I can control it’) cheap terazosin 5 mg without prescription pulse pressure 29. Health locus of control The internal versus external dimension of attribution theory has been specifically applied to health in terms of the concept of a health locus of control discount 5 mg terazosin otc arrhythmia in 7 year old. Individuals differ as to whether they tend to regard events as controllable by them (an internal locus of control) or uncontrollable by them (an external locus of control) cheap terazosin 2mg free shipping arrhythmia jaw pain. Wallston and Wallston (1982) developed a measure of the health locus of control which evaluates whether an individual regards their health as controllable by them (e. For example, if a doctor encourages an individual who is generally external to change their life- style, the individual is unlikely to comply if they do not deem themselves responsible for their health. Although, the concept of a health locus of control is intuitively interesting, there are several problems with it: s Is health locus of control a state or a trait? Unrealistic optimism Weinstein (1983, 1984) suggested that one of the reasons why people continue to practise unhealthy behaviours is due to inaccurate perceptions of risk and susceptibility – their unrealistic optimism. He asked subjects to examine a list of health problems and to state ‘compared to other people of your age and sex, what are your chances of getting [the problem] greater than, about the same, or less than theirs? Weinstein called this phenomenon unrealistic optimism as he argued that not everyone can be less likely to contract an illness. Weinstein (1987) described four cognitive factors that contribute to unrealistic optimism: (1) lack of personal experience with the problem; (2) the belief that the problem is preventable by individual action; (3) the belief that if the problem has not yet appeared, it will not appear in the future; and (4) the belief that the problem is infrequent. In an attempt to explain why individuals’ assessment of their risk may go wrong, and why people are unrealistically optimistic, Weinstein (1983) argued that individuals show selective focus. He claimed that individuals ignore their own risk-increasing behaviour (‘I may not always practise safe sex but that’s not important’) and focus primarily on their risk-reducing behaviour (‘but at least I don’t inject drugs’). He also argues that this selectivity is compounded by egocentrism; individuals tend to ignore others’ risk-decreasing behaviour (‘my friends all practise safe sex but that’s irrelevant’). Therefore, an individual may be unrealistically optimistic if they focus on the times they use condoms when assessing their own risk and ignore the times they do not and, in addition, focus on the times that others around them do not practise safe sex and ignore the times that they do. In one study, subjects were required to focus on either their risk-increasing (‘unsafe sex’) or their risk-decreasing behaviour (‘safe sex’). Subjects were allocated to either the risk-increasing or risk-decreasing condition. Subjects in the risk-decreasing condition were asked questions such as ‘since being sexually active how often have you tried to select your partners carefully? The results showed that focusing on risk- decreasing factors increased optimism by increasing perceptions of others’ risk. There- fore, by encouraging the subjects to focus on their own healthy behaviour (‘I select my partners carefully’), they felt more unrealistically optimistic and rated themselves as less at risk compared with those who they perceived as being more at risk. The stages of change model The transtheoretical model of behaviour change was originally developed by Prochaska and DiClemente (1982) as a synthesis of 18 therapies describing the processes involved in eliciting and maintaining change. Prochaska and DiClemente examined these different therapeutic approaches for common processes and suggested a new model of behaviour change based on the following stages: 1 Precontemplation: not intending to make any changes. These stages, however, do not always occur in a linear fashion (simply moving from 1 to 5) but the theory describes behaviour change as dynamic and not ‘all or nothing’. For example, an individual may move to the preparation stage and then back to the contemplation stage several times before progressing to the action stage. Furthermore, even when an individual has reached the maintenance stage, they may slip back to the contemplation stage over time. The model also examines how the individual weighs up the costs and benefits of a particular behaviour. In particular, its authors argue that individuals at different stages of change will differentially focus on either the costs of a behaviour (e. For example, a smoker at the action (I have stopped smoking) and the maintenance (for four months) stages tend to focus on the favourable and positive feature of their behaviour (I feel healthier because I have stopped smoking), whereas smokers in the precontemplation stage tend to focus on the negative features of the behaviour (it will make me anxious). The stages of change model has been applied to several health-related behaviours, such as smoking, alcohol use, exercise and screening behaviour (e. If applied to smoking cessation, the model would suggest the following set of beliefs and behaviours at the different stages: 1 Precontemplation: ‘I am happy being a smoker and intend to continue smoking’. This individual, however, may well move back at times to believing that they will con- tinue to smoke and may relapse (called the revolving door schema). The stages of change model is increasingly used both in research and as a basis to develop interventions that are tailored to the particular stage of the specific person concerned. For example, a smoker who has been identified as being at the preparation stage would receive a different intervention to one who was at the contemplation stage. However, the model has recently been criticized for the following reasons (Weinstein et al. Researchers describe the difference between linear patterns between stages which are not consistent with a stage model and discontinuity patterns which are consistent. Such designs do not allow conclusions to be drawn about the role of different causal factors at the different stages (i. Experi- mental and longitudinal studies are needed for any conclusions about causality to be valid. These different aspects of health beliefs have been integrated into structured models of health beliefs and behaviour. For simplicity, these models are often all called social cognition models as they regard cognitions as being shared by individuals within the same society. However, for the purpose of this chapter these models will be divided into cognition models and social cognition models in order to illustrate the varying extent to which the models specifically place cognitions within a social context. Cognition models describe behaviour as a result of rational informa- tion processing and emphasize individual cognitions, not the social context of those cognitions. This section examines the health belief model and the protection motivation theory. However, over recent years, the health belief model has been used to predict a wide variety of health-related behaviours. The original core beliefs are the individual’s perception of: s susceptibility to illness (e. More recently, Becker and Rosenstock (1987) have also suggested that perceived control (e. This will also be true if she is subjected to cues to action that are external, such as a leaflet in the doctor’s waiting room, or internal, such as a symptom perceived to be related to cervical cancer (whether correct or not), such as pain or irritation. Norman and Fitter (1989) examined health screening behaviour and found that perceived bar- riers are the greatest predictors of clinic attendance. Several studies have examined breast self-examination behaviour and report that barriers (Lashley 1987; Wyper 1990) and perceived susceptibility (Wyper 1990) are the best predictors of healthy behaviour. Research has also provided support for the role of cues to action in predicting health behaviours, in particular external cues such as informational input. In fact, health promotion uses such informational input to change beliefs and consequently promote future healthy behaviour.

Some feel they need a boost to maintain a high performance level especially after being on duty for so many hours without sleep cheap terazosin 5mg pulse pressure 2012. The information used to diagnose personal illness is subjective and as the craving for the medication increases it interferes with the objective reasoning that the healthcare provider normally uses when assessing patients cheap terazosin 5mg overnight delivery blood pressure is determined by. Even under tight controls buy 2mg terazosin with visa hypertension journal article, drugs can be diverted by healthcare professionals with little chance of being caught generic terazosin 1 mg online arteriovenous malformation. For example, they may give the patient half the prescribed dose and keep the other half for themselves. The fastest way to get to that state of mind may be to take a pill or inject a drug. Detecting Substance Abuse The term “substance abuser” conjures images of an unkempt, malnourished per- son who sleeps on the streets. In reality, the person working alongside you or liv- ing in the house across the street from you could be a substance abuser because many substance abusers go to great lengths to hide their addiction. However, no matter how well substance abusers try to conceal their addic- tion, eventually the addiction causes them to change and it is those changes that become signs of substance abuse. Simple tasks can become overwhelming and eventually an addicted individual will become scattered or disorganized. Trying to add a column of numbers or serve food to customers will become confusing and an individual may be unable to decide what to do first. Individuals simply don’t wake up to go to work or experience periods of withdrawal from reality that result in an inability to remember to go to work or school. One reason is the simple fact that nothing really matters anymore except getting more of the drug. In addition, the disorgani- zation and frequent absences make a drug abuser an unpopular colleague. Co- workers begin to suspect there is a problem and put pressure on the individual to “clean up their act. The addicted individual may be unaware of how they look or even forget to take a shower and change clothing regularly. The need to find more of the drug can also be time consuming and interfere with regular activi- ties that include personal hygiene. Frequently a drug abuser will make a great effort to appear normal during working or school hours. However, after hours may become the time to take more of the drug and the side effects are more pronounced or obvious. For example, physicians work independently and come under scrutiny only in a healthcare facility setting. Furthermore, healthcare profes- sionals have the capability to self-diagnose and to self-treat and may not have another provider complete an objective assessment which might reveal substance abuse. Acknowledging substance abuse may put the individual at risk of sus- pension or revocation of the license to practice. There can also be a “white wall of silence” among healthcare professionals when it comes to reporting a colleague for substance abuse. Although they want to help their colleague, no one wants to be responsible for a colleague losing his or her license—or expose themselves to inadvertently making false accusations. First, there is an ethical obligation to report suspected abuse to protect patients who are being treated by the health- care provider. Healthcare facilities and regulatory boards are sensitive to the need to maintain confidentiality during the handling of the allegation and sub- sequent inquiry. Second, the addicted person actually becomes a patient and should be given the best and most appropriate care. Keeping silent about suspicion of addiction is actually harm- ful to the substance abuser and violates the ethical responsibilities of the health- care provider. This Act requires employers to continue employment of a substance abuser as long as the employee can perform their job function and is not a threat to safety or property. This means that the healthcare provider’s responsibility might be temporarily reassigned until treatment is completed. Many businesses, government agencies, and healthcare facilities require prospective employees to be screened for drugs. In addition, employees might be required to undergo random drug testing or drug testing under special circumstances (such as medication unaccounted for in their work area). Urine testing can detect drugs used days or even a week before the test is performed. As false positive and false negative results can occur, caution should be used when interpreting the results. When asked if they are taking any kind of medication, individuals should include prescription, over-the-counter, and herbal remedies. For example, traces of diphenhydramine (Benadryl)—a commonly used antihistamine medication—will be found in urine and will cause the person to test positive for methadone. Whenever the result of a urine test is found to be positive for drugs, the per- son should undergo another test for that specific medication to confirm the results. The second test is used to identify a false positive that might be gener- ated by the first test. Again, urine testing is done but the request is to screen only for the specific drug identified in the first test. Drug testing only gives evidence that the individual has used or been exposed to a drug but does not indicate any pattern of drug use or the degree of depend- ency. Table 4-1 shows the length of time that traces of popular drugs remain in the body. Drug Description Xanthines A class of drugs that include caffeine and are used in coffee, tea, chocolate, and colas. Anticholinergics A class of drugs that includes Robinal, which is referred to as the “date rape” drug. Amphetamines A class of drugs that includes dextroamphetamine, “dexies,” and methamphetamine (commonly referred to as “speed” and “crystal meth”). Heroin is a pro-drug and is converted in the liver to morphine with the same side effects. Side effects include sedation, decreased blood pressure, increased sweating, flushed face, constipation, dizziness, drowsiness, nausea and vomiting. This medication is commonly used in overdoses and can cause serious kidney problems and death. Aspirin abuse can cause gastric (stomach) irritation which can lead to ulcers and subsequent gastric hemorrhage (bleeding). Several of the side effects include episodes of violent and aggressive behavior, seizures, delirium, and other withdrawal reactions. Diazepam Commonly known as Valium it is used for short-term relief of anxiety symptoms.