Gooding Institute of Nurse Anesthesia. D. Sivert, MD: "Buy Luvox online in USA - Quality Luvox online".

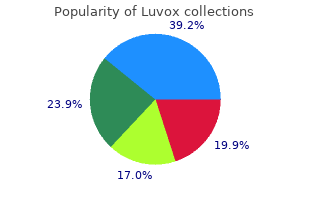

The 10 most frequently implicated drugs were: amoxicillin-clavulanate order luvox 50mg without a prescription anxiety upon waking, flucloxacillin order 100mg luvox free shipping anxiety symptoms lingering, erythromycin order luvox 100mg with mastercard anxiety 2 calm, diclofenac 100 mg luvox fast delivery anxiety 25 mg zoloft, sulfamethoxazole/Trimethoprim, isoniazid, disulfiram, Ibuprofen and flutamide [12–14,21]. Drugs with an intermediate risk were amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and cimetidine, with a risk of one per 10 per 100,000 users [24]. The limitations of this study were the retrospective design with a lack of complete data regarding diagnostic testing and a lack of data on over-the-counter drugs and herbal agents [24]. Amoxicillin-clavulanate-induced liver injury was found in one of 2350 outpatient users, which was higher among those who were hospitalized already, one of 729. This might be due to a detection bias, with more routine testing of the liver in the hospital, but it cannot be excluded that sicker patients are more susceptible to liver injury from this drug. The incidence rates were higher than previously reported, with the highest being one of 133 users for azathioprine and one of 148 for infliximab. Acknowledgments: No specific grants were obtained for research work presented in this paper and no funds for publishing in open access. Discrepancies in liver disease labeling in the package inserts of commonly prescribed medications. Categorization of drugs implicated in causing liver injury: Critical assessment based upon published case reports. Evolution of the Food and Drug Administration approach to liver safety assessment for new drugs: Current status and challenges. Drug-induced liver injury: An analysis of 461 incidences submitted to the Spanish registry over a 10-year period. Causes, clinical features, and outcomes from a prospective study of drug-induced liver injury in the United States. Incidence, presentation and outcomes in patients with drug-induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland. Single-center experience with drug-induced liver injury from India: Causes, outcome, prognosis, and predictors of mortality. The increased risk of hospitalizations for acute liver injury in a population with exposure to multiple drugs. A review of epidemiologic research on drug-induced acute liver injury using the general practice research data base in the United Kingdom. Acute and clinically relevant drug-induced liver injury: A population based case-control study. Sigurdsson and Gudmundur Thorgeirsson 1Solvangur Health Center of Hafnarfjo¨ rdur, 2Department of Family Medicine, University of Iceland, 3Department of Medicine, National University Hospital of Iceland. The article overviews the risk factors for cardiovascular disease and the strategies for primary prevention. An almost Strategies of primary prevention world-wide epidemic of obesity and diabetes is pre- For people at extraordinarily high risk, an individua- dicted for the future, not the least in the densely lised, patient-based approach is both a rational and populated countries of Asia, with consequences of an effective strategy. In the Nurse’s Health Study, women who ate a individuals can be identified and targeted for effective healthy diet, did not smoke, consumed a moderate intervention. In the Framingham study, hypertension amount of alcohol, exercised regularly and maintained was found to occur in isolation only about 20% of the time, but frequently coexisted with risk factors such as Table I. Although each risk factor is a public health problem in itself, they interact Modifiable Non-modifiable Á/ synergistically damaging the vasculature Á/ and have Smoking Age a tendency to cluster. Firstly, the risk relations are contin- independently or via the major risk factors, i. Behavioural change vention refers to both preventing the development of will be best accomplished by influencing the commu- disease as well as its risk factors, and primary nity (13). Because of the large number of people near the middle of the distribution, Smoking. Although this is common knowl- North Karelia Project in Finland (14), the Stanford edge, the important role of physicians and other health Three Community Study (15) and ‘‘Live for Life’’ care providers in helping people to stop smoking is less health promotion programme in Sweden (16). The simple The high-risk and population-based strategies are advice from a physician to stop smoking has been far from being mutually exclusive. On the contrary, shown to double the spontaneous rates of quitting in a they are mutually supportive. As many opportunities interventions are more likely to be successful in an as possible in the varied encounters between patients environment where healthy lifestyle habits are widely and the health care system should be used to ask practised. And those who practice high-risk interven- about smoking habits and to offer assistance to those tions are important champions and educators of the who are ready to fight the habit. It should, however, be kept in mind that it is an uphill struggle to give up smoking and there are strong commercial and social forces that promote smoking, especially among the young. In some countries a positive change has been noted with the prevalence of smoking decreasing (5,16). Elevated blood pressure is a well- established preventable risk factor for the development of all manifestations of atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease, stroke, peripheral artery disease and heart Fig. The aim of primary blood pressure is an equally strong risk factor as prevention is to shift the curve toward the left, i. Both mendations emphasise the importance of repetitive sets of guidelines emphasise that recommendations measurements of blood pressure, sometimes over a must be based not only on lipid measurements but also period of several months, for the accurate assessment on assessment of the absolute coronary risk projected of blood pressure Á/ which is needed for the decision by a total risk profile. L may require cholesterol-lowering drug treatment in Fundamental to that decision is the assessment of a patient with high overall coronary risk, whereas a the patient’s overall cardiovascular risk profile, be- serum cholesterol level of 7Á/8 mmol/L may be left cause the detrimental impact of blood pressure is untreated, except for lifestyle advice, in an individual determined by the presence or absence of other risk with low absolute risk (7). Lifestyle calls for lifestyle recommendations for a period of a interventions are important and in some cases can be few months, and if risk reduction is insufficient drug sufficient for adequate control. The safety and tions should be given to all patients considered to have efficacy of statin therapy in the primary prevention hypertension. Weight control, reduction in the use of setting is based on robust trial evidence (31). Drug below 3 mmol/L is ideal for the whole population and treatment is recommended if the systolic blood a worthwhile public health goal is to achieve these pressure is ]/160 and/or diastolic pressure ]/100 levels with appropriate diet and regular physical mmHg, despite lifestyle interventions. Risk factor saturated fats and cholesterol in a given population management in this patient group is extremely im- and the usual levels of serum cholesterol in that portant. Consequently, in viously discussed, a population strategy should be newly published recommendations from the American augmented by the individualised clinical approach of Diabetes Association, the target goal for hypertensive physicians identifying those who need urgent and treatment among diabetes patients is set at B/130/80 aggressive risk factor modification, including drug mmHg, and it is recommended that this should be treatment and family screening. Most recently, the beginning in childhood, should be one of the most Steno-2 study from Denmark (39) has demonstrated important health priorities for the years to come. The intensive treatment relative risk as smoking, hypercholesterolaemia or involved stepwise introduction of lifestyle and phar- hypertension (47). Part of its complex effect may be included reduced intake of dietary fat, regular parti- mediated through enhanced fibrinolytic potential cipation in light or moderate exercise and abstinence and reduced platelet adhesiveness and thus reduced from smoking. Epidemiological stu- even in small doses aspirin can do more harm than dies have shown that the relationship between body good (54Á/56). Although the reduction in relative risk weight and mortality rate is J-shaped, the lowest may be similar in both primary and secondary mortality rate being among those with ‘‘normal’’ prevention, i.

Syndromes

- Eye pain or soreness

- Get shots to prevent blood clots

- Breathing difficulty

- Atherosclerosis

- Fatigue

- Uneven skin folds of thigh or buttocks

- Paint

- Urinalysis

Strategies for making a medical diagnosis There are several diagnostic strategies that clinicians employ when using patient data to make a diagnosis order luvox 100 mg overnight delivery anxiety symptoms for hours. These are presented here as unique methods even though most clinicians use a combination of them to make a diagnosis order luvox 50mg overnight delivery anxiety meme. Pattern recognition is the spontaneous and instantaneous recognition of a previously learned pattern cheap 50mg luvox amex anxiety symptoms from work. It is usually the starting point for creating a differ- ential diagnosis and determines those diagnoses that will be at the top of the list generic luvox 100mg free shipping anxiety symptoms upper back pain. Usually, an experienced clinician will be able to sense when the pattern is not characteristic An overview of decision making in medicine 229 of the disease. This occurs when there is a rare presentation of common disease or common presentation of a rare disease. An experienced doctor knows when to look beyond the apparent pattern and to search for clues that the patient is pre- senting with an unusual disease. Premature closure of the differential diagnosis is a pitfall of pattern recognition that is more common to neophytes and will be discussed at the end of this chapter. The multiplebranchingstrategy is an algorithmic approach to diagnosis using a preset path with multiple branching nodes that will lead to a correct final conclusion. These are tools to assist the clinician in remembering the steps to make a proper diagnosis. More complex diagnostic decision tools can be of greater help when used with a computer. The strategy of exhaustion, also called diagnosis by possibility, involves “the painstaking and invariant search for but paying no immediate attention to the importance of all the medical facts about the patient. Although, more often than not, this technique will usually come up with the correct diagnosis, the process is time consuming and not cost-effective. A good example of this can be found in the Case Records of the Massachusetts General Hospital feature found in each issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. This strategy is most helpful in diag- nosing very uncommon diseases or very uncommon presentations of common diseases. The hypothetico-deductive strategy, also called diagnosis by probability, involves the formulation of a short list of potential diagnoses from the earliest clues about the patient. Initial hypothesis generation is based on pattern recog- nition to suggest certain diagnoses. This basic differential diagnosis is followed by the performance of clinical maneuvers and diagnostic tests that will increase or decrease the probability of each disease on the list. Further refinement of the differential results in a shortlist of diagnoses and the further testing or the initi- ation of treatment will lead to the final diagnosis. This is the best strategy to use and will lead to a correct diagnosis in most cases. A good example of this can be found in the Clinical Decision Making feature found frequently and irregularly in the New England Journal of Medicine. Heuristics: how we think Heuristics are cognitive shortcuts used in prioritizing diagnoses. The probability that a diagnosis is thought of is based upon how closely its essential features resemble the features of a typical description of the disease. This is analogous to the process of pattern recognition and is accurate if a physician has seen many typical and atypical cases of common diseases. It can lead to erroneous diagnosis if one initially thinks of rare diseases based upon the patient presentation. For example, because a child’s sore throat is described as very severe, a physician might immediately think of gonorrhea, which is particularly painful. The severity of the pain of the sore throat represents gonorrhea in diagnostic thinking. To ignore or minimize the more common causes of sore throat, thinking of a rare disease more often than a common one, is incorrect. Remember that unusual or rare presentations of common diseases such as strep throat, occur more often than common presentations of rare diseases such as pha- ryngeal gonorrhea. The probability of a diagnosis is judged by the ease with which the diagnosis is remembered. The diagnoses of patients that have been most recently cared for are the ones that are brought to the forefront of one’s consciousness. If a physician recently took care of a patient with a sore throat who had gon- orrhea, he or she will be more likely to look for that as the cause of sore throat in the next patient even though this is a very rare cause of sore throat. The availability heuristic is much more problematic and likely to occur if a recently missed diagnosis was of a rare and serious disease. This heuristic refers to the reality that special characteristics of a patient are used to estimate the probability of a given diagnosis. A differential diagnosis is initially formed and additional infor- mation is used to increase or decrease the probability of disease. This tech- nique is the way we think about most diagnoses, and is also called the com- peting hypotheses heuristic. For example, if a patient presents with a sore throat, the physician should think of common causes of sore throat and come up with diagnoses of either a viral pharyngitis or strep throat. After getting more history and doing a physical examina- tion the physician decides that the characteristics of the sore throat are more like a viral pharyngitis than strep throat. This is the adjustment, and as a result, the other diagnoses on the differential diagnosis list are considered extremely unlikely. The adjustment is based on diagnostic information from the history and physical examination and from diagnostic tests. Throughout the patient encounter, new information An overview of decision making in medicine 231 Fig. The problem of premature closure of the differential diagnosis One of the most common problems novices have with diagnosis is that they are unable to recognize atypical patterns. This common error in diagnostic think- ing occurs when the novice jumps to the conclusion that a pattern exists when in reality, it does not. There is a tendency to attribute illness to a common and often less serious problem rather than search for a less likely, but potentially more seri- ous illness. It rep- resents removal from consideration of many diseases from the differential diag- nosis list because the clinician jumped to a too early conclusion on the nature of the patient’s illness. Even experienced clin- icians can make this mistake, thinking that a patient has a common illness when, in fact, it is a more serious but less common one. No one expects the clinician to always immediately come up with the correct diagnosis of a rare presentation or a rare disease. However, the key to good diagnosis is recogniz- ing when a patient’s presentation or response to therapy is not following the pattern that was expected, and revisiting the differential diagnosis when this occurs.

William Stuntz observed effective 50mg luvox anxiety emoji, “the law of search and seizure disfavors drug law enforcement operations in upscale (and hence predominantly white) neighborhoods: serious cause is required to get a warrant to search a house buy luvox 50 mg online anxiety symptoms fear, whereas it takes very little for police to initiate street encounters” (Stuntz 1998 order 50mg luvox with amex anxiety reduction techniques, p order luvox 50mg fast delivery anxiety unspecified icd 10. Residents of middle- and upper-class white neighborhoods would also most likely object vigorously if they were subjected to aggressive drug law enforcement and, unlike low-income minority residents, they possess the economic resources and political clout to force politicians and the police to pay attention to their concerns. The bottom line is that it is “much more difficult, expensive, and politically sensitive to attempt serious drug enforcement in predominantly white and middle-class communities” (Frase 2009, p. Subscriber: Univ of Minnesota - Twin Cities; date: 23 October 2013 Race and Drugs A self-fulfilling prophecy may be at work. If police target minority neighborhoods for drug arrests, the drug offenders they encounter will be primarily black or Hispanic. Darker faces become the faces of drug offenders, which may also contribute to racial profiling. Extensive research shows that police are more likely to stop black drivers than whites, and they search more stopped blacks than whites, even though they do not have a valid basis for doing so. Similarly, blacks have been disproportionately targeted in “stop and frisk” operations in which police searching for drugs or guns temporarily detain, question, and pat down pedestrians (Fellner 2009). Although police generally find drugs, guns, or other illegal contraband at lower rates among the blacks they stop than the whites, the higher rates at which blacks are stopped result in greater absolute numbers of arrests (Tonry 2011). Race becomes one of the readily observable visual clues to help identify drug suspects, along with age, gender, and location. There is a certain rationality to this—if you are in poor black neighborhoods, drug dealers are more likely to be black” (1998, p. Katherine Beckett and her colleagues showed that drug arrests in Seattle reflected racialized perceptions of drugs and their users (Beckett et al. Although the majority of those who shared, sold, or transferred serious drugs were white, almost two-thirds (64. Black drug sellers were overrepresented among those arrested in predominantly white outdoor settings, in racially mixed outdoor settings, and even among those who were arrested indoors. Three- quarters of outdoor drug possession arrests involving powder cocaine, heroin, crack cocaine, and methamphetamines were crack-related even though only one-third of the transactions involved that drug. The disproportionate pattern of arrests resulted from the police department’s emphasis on the outdoor drug market in the racially diverse downtown area of the city, its lack of emphasis on outdoor markets that were predominantly white, and, most important, its emphasis on crack. Crack was involved in one-third of drug transactions but three-quarters of drug delivery arrests; blacks constituted 79 percent of crack arrests. The researchers could not find racially neutral explanations for the police emphasis on crack in arrests for drug possession or sale, or for the concentration of enforcement activity in the racially diverse downtown area rather than predominantly white outdoor areas or indoor markets. These emphases did not appear to be products of the frequency of crack transactions compared to other drugs, public safety or public health concerns, crime rates, or citizen complaints. The researchers concluded that the choices reflected ways in which race shapes police perceptions of who and what constitutes the most pressing drug problems. Blacks are disproportionately arrested in Seattle because of “the assumption that the drug problem is, in fact, a black and Latino one, and that crack, the drug most strongly associated with urban blacks, is ‘the worst’” (Beckett et al. In 2010, as Table 4 shows, cocaine (including crack) and heroin arrests accounted for 22. Blacks were more likely than whites to report using heroin, but the percentages are quite low: 1. The proportion of drug arrests for cocaine and heroin thus seem to bear only a slight relationship to the prevalence of their use. Boyum, Caulkins, and Kleiman (2011) observe that the enforcement of laws criminalizing cocaine accounts for “about 20 percent of the nation’s law enforcement, prosecution, and corrections” (p. Subscriber: Univ of Minnesota - Twin Cities; date: 23 October 2013 Race and Drugs Table 4 Arrests by Type of Offense, Drug, and Race, 2010 White Black Native American Asian Total Sales Cocaine/Heroin 34,787 45,635 346 351 81,119 42. All other things being equal, one would expect the racial distribution of prisoners sentenced for particular crimes to reflect the racial distribution of arrests for those crimes. Blumstein showed in 1982 that about 80 percent of racial differences in incarceration in 1979 could be accounted for by differences in arrest (Blumstein 1982). In the case of drug offenses, there was a significant difference between the racial breakdowns of arrests and incarceration. Racial disparities in imprisonment for drug crimes are even greater than disparities in arrest. There are significant racial differences at different decision points in criminal justice processing of cases following arrest. Those differences compound, ultimately producing stark differences in outcomes (Kochel, Wilson, and Mastrofski 2011; Spohn 2011). In Illinois, for example, even after accounting for possible selection bias at each stage of the criminal justice system, nonwhite arrestees were more likely than whites to have their cases proceed to felony court, to be convicted, and to be sent to prison (Illinois Disproportionate Impact Study Commission 2010). After controlling for other variables, including criminal history, African Americans in Cook County, Illinois were approximately 1. Subscriber: Univ of Minnesota - Twin Cities; date: 23 October 2013 Race and Drugs Spohn 2011). Young African-American men in Ohio had lower odds of pretrial release on their own recognizance, had higher bond amounts, and higher odds of incarceration relative to other demographic subgroups (Wooldredge 2012). The exercise of federal prosecutorial discretion with respect to charging decisions, motions for mitigated sentences based on substantial assistance by the defendant in the prosecution of others, and plea bargaining has led to racial disparities that affect sentences (Baron-Evans and Stith 2012, pp. Rehavi and Starr (2012) found that federal prosecutors were more likely to charge more serious offenses against black than white arrestees, including for offenses carrying mandatory minimum penalties. Ulmer and his colleagues found racial differences in downward departures under the federal guidelines, whether initiated by prosecutors or judges (Ulmer, Light, and Kramer 2011). Researchers concluded that the defendant’s race influenced the likelihood of incarceration in 15 studies of drug offender sentencing. All else considered, white felony drug offenders in North Carolina received less severe punishment than blacks or Hispanics (Brennan and Spohn 2011). The effects of race on sentencing decisions is particularly notable when the studies take account of age, gender, or socioeconomic status (Spohn and Hollerman 2000; Doerner and Demuth 2010; Spohn 2011). Doerner and Demuth’s study of sentencing decisions in federal courts found that young black and Hispanic males receive the harshest sentences of all racial/ethnic/gender-age subgroups and that the effects of race and ethnicity were larger in drug than in nondrug cases (Doerner and Demuth 2010, p. In 2003, the United States Sentencing Commission reported that black drug defendants were 20 percent more likely to be sentenced to prison than white drug defendants (U. In its annual report for 2010, the United States Sentencing Commission reported that black (30. Blacks had higher average sentences than whites or Hispanics for powder and crack offenses, regardless of whether they were sentenced under the mandatory minimum provisions (U. Much of the research on racial disparities in case outcomes has sought to tease out the extent to which racial differences reflect the influence of legally irrelevant factors such as race, gender, and age. Yet research also shows that ostensibly race-neutral, legally relevant factors such as prior criminal records yield racial disparities. Sentencing enhancements for repeat offenders are ubiquitous, both formally in sentencing laws and informally in sentencing practices. They may play a particularly significant role in drug cases because many drug defendants have significant histories of prior offending.

When the researcher attempted to make this information known to authorities at the uni- versity buy 50mg luvox mastercard anxiety symptoms racing heart, the company threatened legal action and the researcher was removed 92 Essential Evidence-Based Medicine from the project buy cheap luvox 50mg online anxiety 24 hour helpline. When other scientists at the university stood up to support the researcher buy luvox 100mg with mastercard anxiety symptoms at bedtime, the researcher was fired purchase luvox 100mg fast delivery anxiety attack symptoms quiz. When the situation became public and the government stepped in, the researcher was rehired by the university, but in a lower position. The issues of conflict of interest in clinical research will be dis- cussed in more detail in Chapter 16. If readers think bias exists, one must be able to demonstrate how that bias could have affected the study results. Benjamin Disraeli, Earl of Beaconsfield (1804–1881) Learning objectives In this chapter you will learn: r evaluation of graphing techniques r measures of central tendency and dispersion r populations and samples r the normal distribution r use and abuse of percentages r simple and conditional probabilities r basic epidemiological definitions Clinical decisions ought to be based on valid scientific research from the medical literature. The competent interpreter of these studies must understand basic epidemiolog- ical and statistical concepts. Critical appraisal of the literature and good medical decision making require an understanding of the basic tools of probability. It is virtually impossible to describe the operations of a given biological system with a single, simple formula. Since we cannot mea- sure all the parameters of every biological system we are interested in, we make approximations and deduce how often they are true. Because of the innate vari- ation in biological organisms it is hard to tell real differences in a system from random variation or noise. Statistics seek to describe this randomness by telling us how much noise there is in the measurements we make of a system. By filter- ing out this noise, statistics allow us to approach a correct value of the underlying facts of interest. These include techniques for graphically displaying the results of a study and mathematical indices that summarize the data with a few key numbers. These key numbers are measures of central tendency such as the mean, median,andmode and measures of dispersion such as standard devia- tion, standard error of the mean, range, percentile,andquartile. In medicine, researchers usually study a small number of patients with a given disease, a sample. What researchers are actually interested in finding out is how the entire population of patients with that disease will respond. Researchers often compare two samples for different characteristics such as use of certain therapies or exposure to a risk factor to determine if these changes will be present in the population. Inferential statistics are used to determine whether or not any differences between the research samples are due to chance or if there is a true difference present. Also inferential statistics are used to determine if the data gathered can be generalized from the sample to a larger group of subjects or the entire population. Visual display of data The purpose of a graph is to visually display the data in a form that allows the observer to draw conclusions about the data. The reader is responsible for evaluating the accu- racy and truthfulness of graphic representations of the data. A lack of a well-defined zero point makes small differences look bigger by emphasizing only the upper portion of the scale. It is proper to start at zero, break the line up with two diagonal hash marks just above the zero point, and then continue from a higher value (as in Fig. This still exaggerates the changes in the graph, but now the reader is warned and will consider the results accordingly. Lack of pro- portionality, a much more subtle technique than lack of a well-defined zero, is also improper. It serves to emphasize the drawn-out axis relative to the other less drawn-out axis. This visually exaggerates smaller changes in the axis that is drawn to the larger scale (Fig. Therefore, both axes should have their vari- ables drawn to roughly the same scale (Fig. This makes the change in mean final exam scores appear to be much greater (relatively) than 80 they truly are. Although the change in mean final exam scores still appears to 80 be relatively greater than they truly are, the reader is notified that this distortion is occurring. This consists of the use of three-dimensional shapes to demon- strate the difference between two groups, usually the effect of a drug on a patient outcome. One example uses cones of different heights to demonstrate the dif- ference between the endpoint of therapy for the drug produced by the company and its closest competitor. Visually, the cones represent a larger volume than sim- ple bars or even triangles, making the drug being advertised look like it caused a much larger effect. This makes it appear as if the change in mean 80 final exam scores occurred over a much shorter time period than in reality. The stem is made up of the digits on the left side of each value (tens, hundreds, or higher) and the leaves are the digits on the right side (units, or lower) of each number. Let’s take, for example, the following grades on a hypothetical statistics exam: Review of basic statistics 97 Fig. In creating the stem-and-leaf plot, first list the tens digits, and then next to them all the units digits which have that ‘tens’ digit in common. This can be rotated 90◦ counterclockwise and redrawn as a bar graph or his- togram. The x-axis shows the categories, the tens digits in our example, and the y-axis shows the number of observations in each category. The y-axis can also show the percentages of the total that each observation occurs in each category. This shows the relationship between the independent variable, in this case the exam scores, and the dependent variable, in this instance the number of students with a score in each 10% increment of grades. As a rule, the author should attempt to make the contrast between bars on a histogram as clear as possible. The central line in the box is the median, the middle value of the data as will be described below. The box edges are the 25th and 75th percentile values and the lines on either side represent the limits of 95% of the data. Measures of central tendency and dispersion There are two numerical measures that describe a data set, the central tendency and the dispersion. There are three measures of central tendency, describing the center of a set of variables: the mean, median, and mode. In this equation, xi is the numeri- cal value of the i th data point and n is the total number of data points. These are extreme numbers on either the high or low end of the distribution that will produce a high degree of skew.

Order luvox 100 mg on line. Five Simple Tips To Avoid Stress And Anxiety | Quotes About Life.