Franklin Pierce Law Center. D. Oelk, MD: "Order Diflucan online - Safe online Diflucan no RX".

Lillywhite Professor generic diflucan 150mg with visa antifungal foods and herbs, Department of Communicative Disorders and Deaf Education cheap 50 mg diflucan with visa fungus zombie humans, Utah State University purchase 50 mg diflucan visa fungus candida albicans, 2610 Old Main Hill cheap diflucan 50mg overnight delivery antifungal medications for dogs, Logan, Utah 84322 Dr. Gillam’s research, which has been funded by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders and the U. Department of Education, primar- ily concerns information processing, language assessment, and language intervention with school-age children with language impairments. Gillam has been the associate editor of the American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology (1996–1999) and the Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research (2001–2004; 2010–2013). Gillam has published three tests and two other books—Memory and Language Impairment in Children and Adults (Aspen, 1988) and Communication Sciences and Disorders: From Science to Clinical Practice (co-edited with Thomas Marquardt & Fredrick Martin; Singular, 2000; Jones & Bartlett, 2010, 2015). In addition to reviewing a model of intervention structure, we summarize trends in treatment development and implementation that serve as a backdrop for current and future actions by both researchers and clinicians. We also suggest ways that different audiences can take advantage of the book for their own purposes—placing great- est emphasis on how to use the intervention descriptions to inform decisions about whether and how to incorporate each intervention into plans for the management of language disorders in children. We introduce 14 evidence-based language interventions for children, and we provide specific infor- mation on how to conduct each treatment. Furthermore, we highlight claims of val- ue associated with each treatment approach and facilitate readers’ evaluations and comparisons of the interventions in terms of their clinical procedures and the extent of their research base. We want to help readers develop strategies for accessing and interpreting the complex web of information that constitutes evidence that does and does not support the value of an intervention. We consequently have planned the book’s organization carefully, recruited outstanding researchers as chapter authors, and diligently edited what they produced with the intent of giving readers the infor- mation they need regarding when a decision to use an intervention may be judged “evidence based” and how the intervention can be successfully implemented. Furthermore, families of affected children may find this a useful tool for investigating one or more interventions proposed for use with their child. To serve these broader purposes, we offer recommendations regarding how members of these differing audiences might select sections to read or ways to use and supplement the information they obtain. An entire section from the earlier edition that included nonlanguage interventions (e. This means that the book now contains just two sections, with one addressing language problems characteristic of infants, toddlers, and preschoolers and the other targeting problems found in school-age children. We have made significant changes in the interventions included in each section as well. Seven of the original chapters have been updated to reflect ongoing developments as the interventions have continued to be studied and implemented (Chapters 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, and 10). Eight of the interventions from the first edition were not carried over to this edition, for reasons including insufficient fit with the new sectional organization, a lack of new research exploring their use, or their recent description in related volumes. Three of these new chap- ters expand the book’s attention to literacy and its precursors, including chapters on print referencing (Chapter 7), word decoding, reading comprehension (Chapter 11), and narration (Chapter 13). In addition, two of the new chapters target more complex language (Chapter 12) and social communication skills (Chapter 14) and two others address bilingualism (Chapter 9) and service delivery models (Chapter 15). As noted previously, we have included more interventions dealing with written language in this volume. In so doing, we have tried to maintain our focus on children who exhibit or have histories of spoken language disorders and the relationship be- tween these early problems and reading disabilities. Though we have intentionally paid greater attention to interventions targeting skills associated with early reading development, this is not designed to be a book on intervention for children with reading disabilities, per se. The template—a description of content areas and headings used to signal them— was devised to focus on theoretical and empirical information supporting an inter- vention’s use as well as practical and procedural information that can help clinicians determine the intervention’s feasibility for their setting and client population and, possibly, set the clinician on the path to learning and using it. Several relatively small adjustments to the earlier template version are noted in the description that follows. Following a very brief Abstract, a longer Introduction section provides more extensive, but still concise background information. The next section, Target Excerpted from Treatment of Language Disorders in Children, Second Edition by Rebecca J. Content specifications of the template followed within each chapter Section Content Abstract and Introduction Overview and broader introduction to the intervention and the chapter itself, including the specific individuals for whom the intervention is designed, the intervention’s basic focus, and its key methods Target Populations Description of populations for which empirical and/or theoretical sup- port is available with regard to variables such as age, diagnosis, and prerequisite skills Theoretical Basis Outline of the dominant rationale for the intervention, including as- sumptions about the deficit, compensatory strategy or strength that is targeted and the nature of the desired outcomes (e. Practical Requirements Time and personnel demands, including training for all intervention agents (e. Whereas in the earlier edition, discussion of assess- ments used to identify candidates for an intervention was included in this section, Excerpted from Treatment of Language Disorders in Children, Second Edition by Rebecca J. There are many terms that are used by the chapter authors to refer to children who experience significant difficulties learning and using language. The World Health Organization (2001) uses the word impairment to refer to any loss or abnormality of psychological, physiological, or anatomic structure or function. With respect to child language development, most authors have used the term language impair- ment to refer to describe children with significant delays in the development of language comprehension or use. However, most of the authors of the chapters in this volume have decided to refer to these groups separately because they are often treated that way by school assessment teams across the nation. Careful readers will note that the terms language impairment, specific lan- guage impairment, primary language impairment, language disorder, and language learning disability are used by the authors of the chapters of this book. Rather than restrict all the authors to the use of one term and, more importantly, to assign meanings to these terms that are not well recognized in the field, we have allowed authors to use terms of their own preference and to define the terms explic- itly when they have used them to refer to distinctive subgroups of children who have difficulties with language development. Although we risk adding to the terminology confusion, we believe that our use of multiple terms for developmental language difficulties is reflective of the current state of the literature in this area. Interventions often, if not always, are designed in light of more, or less, well-defined models or theories addressing the nature of problems underlying children’s delays or abnormalities in language acquisition and/or the mechanisms by which those prob- lems may be mitigated, resolved, or circumvented to improve a child’s language and communication function. In the Theoretical Basis section, authors are asked to ex- plicate these foundations for their intervention. This section can help a reader deter- mine whether an intervention seems of likely value on a rational basis in the absence of a long history of research or a history that fails to include research specific to the clinician’s caseload or context. The Empirical Basis section presents a summary of the current evidence sup- porting an intervention’s efficacy and effectiveness for specific populations. Thus, it is one of the most important sections for readers wanting to identify interventions with stronger rather than weaker research portfolios (a central tenet of evidence-based practice). When considered by itself, this section admittedly constitutes a narrative review written by committed developers or proponents of the intervention and, as such, is therefore necessarily subject to bias. However, the empirical summaries can orient readers to recent research on the intervention being addressed and provide preliminary accounts of the nature of existing support. In this edition, to bolster the transparency and accessibility of information about the quality of studies being cited, we have asked authors to tabulate levels of evidence for the studies they cite. It has even been argued that parallel evidence from related fields may sometimes prove valuable (e. Although it is always the case that generalizing from research on a group or even a well-described individual (e. Such decisions require greater scrutiny and usually warrant less influence on decision making. On the other hand, strong evidence is usually in short supply; clinicians who have strong evidence supporting use of an Excerpted from Treatment of Language Disorders in Children, Second Edition by Rebecca J. The section titled Overview of Assessment and Decision Making is intend- ed to allow authors to identify measures and methods for determining that a child is a likely candidate for the intervention and for examining how the child is responding to the intervention. Treatment data (which are sometimes referred to as internal ev- idence) are critical to clinical decision making for a given child, beginning with initial decisions about enrollment to ongoing decisions about changes in goals or methods within an intervention, to more final decisions regarding dismissal.

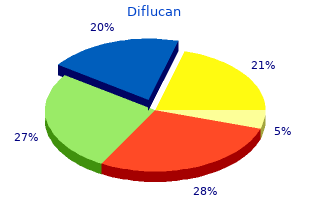

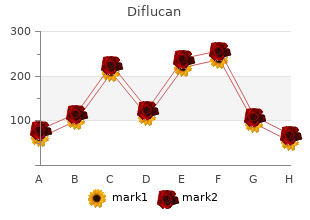

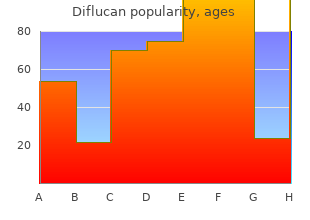

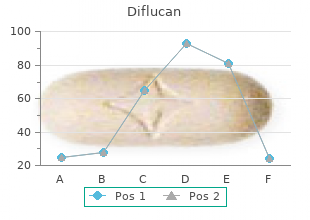

Even earlier studies referred to the problem area of chronic (31/55/59/61/62/65/92/94/121/138) Lyme borreliosis and the limits of its susceptibility to treatment order diflucan 50mg visa fungus eliminator. In all these studies diflucan 50mg overnight delivery anti fungal infection tablets, the duration of treatment was generally limited to a maximum of four weeks buy 150mg diflucan mastercard fungus vs eczema. Considerable therapeutic failure rates occurred under these conditions buy generic diflucan 200mg antifungal ringworm, even with (78/82/90) repeated courses of treatment. The duration of treatment is of decisive importance for the success of antibiotic treatment. There are now a few studies available which provide evidence of the positive effect and the (25/26/27/30/36/44/46/51/52/81/144) safety of long-term antibiotic therapy. The limited effect of antibiotic treatment is documented in numerous studies: Pathogens were cultured even after supposedly highly effective antibiotic ther- (63/74/81/96/119/120/122/139/147) apy. For example, Borrelia were isolated from the skin after multi- (40/61/76/81/122/147) ple courses of antibiotic treatment (ceftriaxone, doxycycline, cefotaxime). A discrepancy was also found between the antibiotic sensitivity of Borrelia in vitro versus in (74) vivo. Moreover, additional factors are involved in vivo which lie in the capability of Borre- (60/83/85/86/120) lia to evade the immune system, specifically under the influence of various (80) antibiotics. Hypothetically, the persistence of Borrelia is attributed to its residency within the cell and to the development of biologically less active permanent forms (sphaeroplasts, encystment) (19/85/86/94/120) among other things. In addition, Borrelia was also shown to develop biofilms with the effect of resisting complement and typical shedding (casting off antibodies from the (83/85/86) surface of the bacterium). The ability of the pathogen to down-regulate proteins (pore-forming protein) might also diminish the (34/74/84) antibiotic effect. There are four randomised studies relating to the therapy of chronic Lyme borrelio- (44/78/82/90) sis, in which different antibiotics were compared when used in the antibiotic treat- ment of encephalopathy. It was shown in these studies that the cephalosporins were supe- (31/62/94/96) rior to penicillin. Doxycycline in its customary dosage resulted in only relatively low serum levels and tissue concentrations, whereas the concentrations in the case of the cephalosporins were markedly higher, i. Of the available antibiotics, tetracyclines, macrolides and betalactams have proved effective in the treatment of Lyme borreliosis. The efficacy of other antibiotics, especially the (20/74/160) carbapenems, telithromycin and tigecycline, is based on in vitro studies. There are (64) no clinical studies except for imipenem, which was given a favourable clinical assessment. The efficiency of a combined antibiotic therapy has not been scientifically attested to date; this form of treatment is based on microbiological findings and on empirical data that have not so far been systematically investigated. As table 5 shows, only the substances metronidazole and hydroxychloroquine have an effect (101) on encysted forms. Hydroxychloroquine assists the action of macrolides and possibly also that of the tetracyclines. This is particu- larly applicable in the case of children and patients with above or below normal weight. Some physicians of the German Borreliosis Society are critical of the use of 3rd generation cephalosporins or of penicillins alone in Lyme borreliosis, because they may possibly favour (101/120) the intracellular residency of Borrelia and its encystment. If ceftriaxone is used, a sonographic check every 3 weeks is necessary to rule out sludge for- mation in the gall bladder. Table 6: Antibiotic monotherapy of Lyme borreliosis In the early stage (localised) Doxycycline 400 mg daily (children of 9 years old and above) Azithromycin 500 mg daily on only 3 or 4 days/week Amoxicillin 3000-6000 mg/day (pregnant women, children) Cefuroxime axetil 2 × 500 mg daily Clarithromycin 500-1000 mg daily Duration dependent on clinical progress at least 4 weeks. In the early stage with dissemination and late stage Ceftriaxone 2 g daily Cefotaxime 2-3 x 4 g Minocycline 200 mg daily, introduced gradually Duration dependent on clinical progress. Corticosteroids should be adminis- tered parenterally only in an emergency, depending on the severity of the reaction. During long-term antibiotic treatment, probiotic treatment should be given to protect the in- testinal flora and to support the immune system (e. Several meta-analyses show that the prophylactic use of probiotics (13/24/28/38/102/127) lowers the risk of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea. The action of macrolides and possibly also of tetracyclines is intensified by the simultaneous administration of hydroxychloroquine, which, like metronidazole, acts on encysted forms of (36) Borrelia. If minocycline is not tolerated, it can be replaced with doxycycline or clarithromycin. Doxycycline and minocycline can be combined with azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine. To make it easier to identify drug intolerance, the treatment should not be started with the individual antibiotics given simultaneously. It is preferable to add the other antibiotics stag- gered over time, say at intervals of one to two weeks. Prevention involves the following factors: • exposure to ticks • protective clothing • repellents • examination of the skin after exposure • removal of ticks that have started feeding. Recurrence is treated again as necessary, but generally in cycles of shorter treatment times, e. With regard to the risk of exposure, it should be noted that ticks wait in grasses and under- growth up to a height of 120 cm above the ground. On contact, the ticks are brushed off the vegetation and can get to all parts of the body across the skin (beneath clothing). Ticks pre- fer moist and warm areas of skin, but a tick bite can basically occur on any part of the body. A particular risk arises also from contact with wild animals and with domesticated animals which are exposed to ticks periodically. The following main sources of risk emerge from this constellation: • private gardens • grass, low undergrowth and similar vegetation • spending time in the countryside • domesticated animals, e. Protective clothing should prevent ticks gaining entry, especially on the arms and legs, by having tight-fitting cuffs. There is special protective clothing available and various repellents which reduce the risk by being applied directly onto the skin or clothing before exposure. However, the repellents are not completely effective and their duration of action is limited to a few hours. The problem with this is that the early stages of the adult ticks, the larvae and nymphs, are only 1 mm in size at best and are therefore easy to miss. A tick that has started feeding must be removed as soon as possible because the risk of in- fection increases with the length of time spent feeding. After grasping it with the tweezers, the tick is pulled slowly and steadily out of the skin. Berkhoffii and Bartonella henselae bacteremia in a father and daughter with neurological disease. This was followed by a repeated, anonymous consultation process in which all ordinary members of the Society and external experts were able to submit, comment and vote on suggested amendments. Rüdiger von Baehr * Specialist in Internal Medicine Institute of Medical Diagnostics, Berlin Dr.